Delegation and Boxes

In documenting Field's inner workings there are two things that are important to understand. One, how properties — variables that are stored in elements in the canvas — work and two, how Field is extended by plugins. Fortunately these two things are actually the same thing.

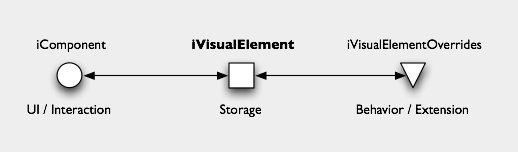

Field's core is constructed out of a few core interfaces, and the most core of this core is iVisualElement. Objects of this class back pretty much everything that appears in Field's canvas — they are associated with the plain boxes that contain code, time markers & sliders, constraints. They also back each plugin and the sheet itself. iVisualElement (the i indicates an interface) is helped by two other interfaces iComponent and iVisualElementOverrides. They are arranged loosely like the classic Model/View/Controller architecture:

- [iComponent] handles anything concerning the drawing of the visual element, and manages it's interactivity (the mouse events for resizing a box are interpreted here, for example). Expect to encounter some pretty raw OpenGL and event handling code in the

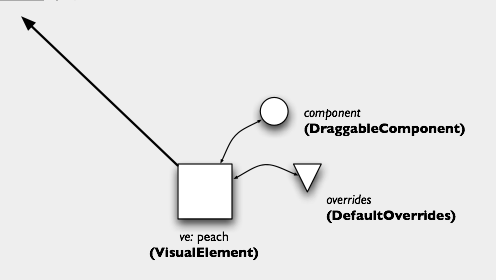

iComponentimplementations. There are only a handful ofiComponentimplementations —DraggableComponentdraws a "vanilla" box with a label and allows resizing and translation;PlainDraggableComponentdraws nothing, but allows resizing and translation of an element's (invisible) frame;PlainComponentdraws nothing and doesn't do anything with the mouse events it receives. - [iVisualElementOverrides] handles anything concerning the behavior of elements. It's here that there's code for limiting how elements are resized, describing menu items, and providing instructions for painting elements. As you might expect, there are a large and ever increasing number of

iVisualElementOverrides. - [iVisualElement] provides the storage and the glue for these classes. It's here that properties are actually stored, including the associated

iComponentandiVisualElementOverridesinstances. It's essentially aMap<VisualElementProperty, Object>. When a Field sheet is saved to disk, it's theiVisualElements that are stored, not theiComponents or theiVisualElementOverrides's (only theirClassis saved). Anything that needs to persist across sessions has to end up inside aniVisualElement. Since it's so simple, there's only really one implementation ofiVisualElement, calledVisualElement.

One more example to help define the roles of these classes: a visual element that draws splines (quite common in Field, right-click on the canvas and select "New Spline Drawer"). In this case we have an iComponent that gets mouse and repaint events; an iVisualElementOverrides that makes it easy for Python code to specify what splines to draw, adds menu items for saving geometry as SVG files &c, and helps control mouse based editing of the resulting splines; and an iVisualElement that keeps hold of the code itself, the resulting splines, the bounding box of the geometry, and so it. Shorter still: 1) providing a place to draw something (iComponent) 2) working out what to draw iVisualElementOverrides, and 3) allowing the drawing to persist iVisualElement.

Delegation and extension

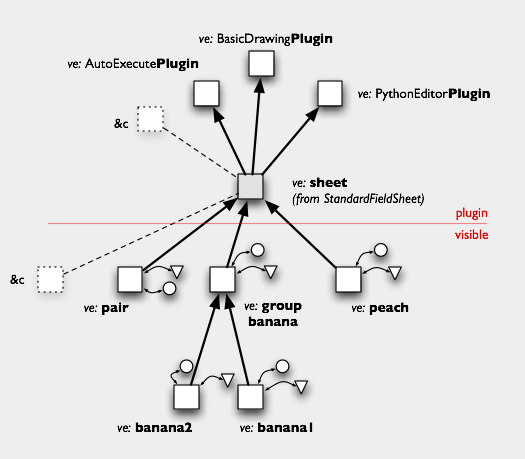

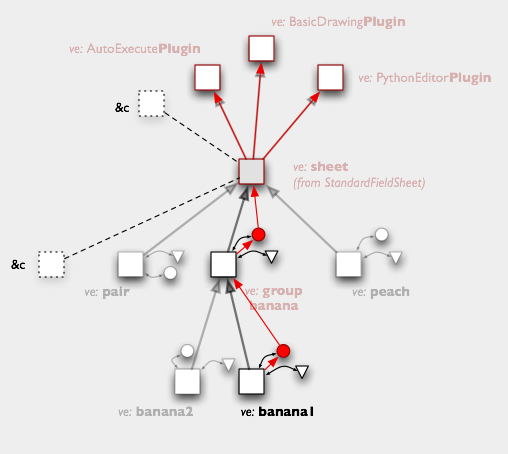

So far, so conventional. But Field's extensibility is a achieved by using a special dispatch system for methods over iVisualElements which are arranged in a directed graph structure. This mechanism means that when one calls a "method" on an iVisualElement's iVisualElementOverrides that instance might decided to both act upon it — invoke that method — and pass it along "up" the directed graph. This passing "up" the graph happens in a breadth-first fashion, and at each step a method can decide to pass it upwards, skip everything above it, or stop the dispatch altogether.

This multiple dispatch / delegation structure seems a little odd at first, but it's not without precedent, it's not even rare. Even the web based collaboration software I'm writing this in right now has a delegation structure for it's templates — Trac creates it's ultimate .css sheets by condensing over page, project and system wide directories; WordPress (used for OpenEndedGroup.com) has a similar strategy for tracking down PHP templating code; OS X looks in a variety of locations (user, system, network ... ) for application preferences; classic object orientation is simply a very particular set of delegation structures. It's a powerful idea that Field uses to compose complexity out of simple parts.

The graph in Field typically looks like this:

In Field, this means that "Plugins" are in actual fact just iVisualElement / iVisualElementOverrides pairs (they don't typically have iComponents associated with them) that sit "high up" in the graph, essentially extending the methods of the iVisualElements below them. For example it's the PythonEditingPlugin that adds the "Delete element" menu item for the currently selected element; and indeed the very ability to execute python code by option-clicking on the element happens here. This is because there are methods in iVisualElementOverrides that are getMenuItemsFor(iVisualElement element and beginExecution(iVisualElement) that are exposed to the plugins by this delegation structure.

Finally, because of the way that

Finally, because of the way that iVisualElementOverides are specified, it's easy to implement an extra dimension of extensibility. iVisualElementOverrides support mixing in other overrides. Behavior offered by any particular iVisualElementOverrides implementations can be added to any iVisualElement.

Most notably, in Python, you can extend Field this way inside Field itself: see ExtendingFieldInField.

Looking up properties happens the same way — properties are searched for all the way up the graph by the simple presence of a getProperty(...) method. This allows the contents of properties themselves to be overridden (for example, python code that's in one visual element can be manipulated before it's executed by the "groups" that it's a member of). Indeed these properties are fundamentally the glue that holds Field together — elements and plugins find other plugins by asking for named properties. See the user-level documentation for Properties.