optics + illusion

A month after finishing Housebound, I am housebound again myself, following the second of two minor foot surgeries in two years.

Day after day on the sofa will have you yearning for the world outside your window, so when your next doctor’s appointment finally comes around again, it’s time for a little happiness.

Which is how it was that last Thursday, after the cab I’d caught to 80th and Columbus had got me there a quarter of an hour early, I hobbled inside a café for an iced tea, then sat myself down on the folksy wooden bench set on the sidewalk just outside its door. The day was bright and warm and dry, and for all of eight minutes I basked in the sunlight, trying to take everything in.

Across Columbus Avenue was the the little park that wraps around the back of the Natural History Museum, but closer at hand was the play of the sidewalk where I found so many things beckoning for my attention — a toddler riding regally by in her stroller, a tattooed furniture mover rolling a brown leather armchair on a diminutive wooden dolly, a high-heeled young beauty teetering past, the medallion at the end of a long chain around her neck striking her chest with every step.

It was actually a scrap of white paper that held my attention longest, skittering across the sidewalk at my feet. A page torn from …? — no, most likely a discarded sandwich wrapper from the bodega a few doors down. A whimsical wind had it going first one way and then another, lifting off briefly into the air then scraping across the rough concrete again, traversing the shadows of a little sapling planted near the curb, with its dark little leaves quivering madly on the leashes of their stems…

And all this part of the swirling dance of detritus on the street, which charmed me with its too-often-overlooked intricacy. I spotted a piece of transparent cellophane that had maintained a bit of its fragile shape, a folded corner suggesting the oblong volume of the original cigarette pack… And then, when the wind picked up, the cellophane went its own merry way while I was distracted by the discarded pages of yesterday’s news spreading broadsheet or tabloid wings to soar sideways a step or two before crumpling back down to earth again…

peripheral vision

A childhood fascination with peripheral vision, which persists to this day, came to me from the stories my father would tell about manning the look-out post on the conning tower of his submarine. He’d always had keen eyesight, but in the Navy he was taught that in the dark of night you can sometimes see more out of the corner of your eye than directly.

Later on, I concentrated on the metaphorical truth of this observation, but more recently I’ve circled back to its literal meaning, which helps explain some of the more interesting aspects of stereopticon imaging.

cross your eyes

Take for example this right-eye shot from Housebound, in which among other things a scrap of paper skitters across the busy intersection in the direction indicated by the added arrow:

In editing the stereo footage, you have to displace the two images slightly to trigger the illusion of depth, tricking your eyes into converging as if onto a real object in real space. You can’t get the right displacement for the whole expanse of the image, but instead have to pick a point to optimize — a point you hope will throw the whole picture into the most compelling perspective.

For this shot, it was that scrap of paper that we picked, and indeed your eyes do resolve it into perfect 3D. However, more interesting is what this does to the rest of the image, much of which you now have to take in peripherally. All of a sudden the slightly blurred pedestrian activity and the nearby play of sunlight assert their presence more forcefully, somehow more lifelike because you apprehend them at the edge of your vision, precisely as you do when navigating a real crosswalk yourself.

adjustable illusion

Our eyes crave meaning, finding it even where there is none (in clouds, in splotches of ink, in the flames of a fire). So too with the illusion of depth, which our eyes conjure up on the scantiest of evidence.

In looking at a stereo image, especially after a little practice, you can force disparate parts of the scene into depth by deliberately shifting the triangulation of your two eyes. Since two sectors of the image rarely have the same displacement of right and left layers, it’s only with this kind of ocular adjustment that you can move around within the space of the image, which feels a bit like traversing the space both of the scene and of your skull.

Nowhere was this made clearer in Housebound than in this shot of pigeons crisscrossing our window view at unexpected speeds, elevations, and depths. It is the birds’ movement that initially makes them visible (the added arrows are needed to make them out in the still).

Your eyeballs keep readjusting to snap a particular flight into focus.

whirlwinds & parades

In New York City, people toss basketballs and they toss trash, sometimes in the same place. Too bad that during the shooting of Housebound it proved so hard to align and focus our ungainly stereo rig, for had it been a quicker process we’d have captured a surprising spectacle that unfolded above the school playground pictured in the shot above (an area just below the view framed by the window in the shot further above).

Strong winds swirled across this wide open space, which was bounded to the west by a large school building and to the east only by Broadway and the subway line that runs aboveground for 13 blocks there. The winds had curved together to form a real whirlwind that picked up a dense array of old newspapers, plastic bags, advertising circulars, and other debris, arcing through the air many feet above the ground in the most amazing fashion.

This manifestation of urban nature put me in mind of the ticker-tape parades in the Canyon of Heroes downtown:

—Ticker-tape in name only nowadays, since stock market updates have long since migrated from paper to computer screen.

Like the chain of so many New York City associations, this one leads back to September 11th, when the jetliner collisions that brought down the twin towers of the World Trade Center also released a storm of paper from all the collapsing offices.

homing

But let me not end this there.

The other day my daughter and I gazed out from our front window over the Harlem plain towards the East River, which could be made out only in the form of the towers of the Triboro Bridge rising above it.

What arrested our attention in the slanting late-afternoon light was a flock of birds that kept circling between two high-rises in the distance. There must have been 50 or more of these birds — pigeons presumably — and they flew as tightly packed together as a cluster of midges on a summer’s day.

As they arced back and forth through the air, they flashed white and then dark as they were caught in sunlight and then in shadow — like the dot-dash of some long forgotten code, elaborated in the old days when pigeon fanciers schooled their rooftop flocks on their tenement roofs and then dispatched them to the skies above the city.

camera obscura

An old trick of optics — that of the camera obscura — once conjured up an unexpectedly enthralling vision.

This was when I’d stumbled upon The Magic Eye at the Cliff House in San Francisco, and found its revolving periscope-style lens taking in Ocean Beach and Seal Rock at the edge of the Pacific.

The landscape reflected within the disc of the mirror below floated like an apparition — so much more vivid somehow than the real thing itself, as it had presented itself to my eyes just moments before outside. Seagulls banked into view, then hovered in the air nearly motionless: suspended by the wind and by the reflection simultaneously, they seemed near enough to touch — but only with a phantom hand of the visual cortex.

Auden puts this best: <div style="margin-left: -25px;width:150px; text-align:right; float:left; font-size:80%; line-height:130%;padding-top:5px; color:#555;"> from “Hic et Ille” in The Dyer’s Hand </div> > As seen reflected in a mirror, a room or a landscape seems more solidly there in space than when looked at directly. In that purely visual world nothing can be hailed, moved, smashed, or eaten, and it is only the observer himself who, by shifting his position or closing his eyes, can change.

##3d — new ish

Sept 2007 Ars Electronica has a permanent Cave facility, so not having been in one for quite a long time, I signed up to take another look. I donned the polarized goggles that flickered in rapid alternation, and stepped into the small crowded chamber. There, sure enough, the walls, ceiling, and floor obliged with that familiar, slightly unreal 3D depth. Once again there came the usual symptoms of motion-sickness, my eyes decidedly disconnected from my other senses.

The main disappointment, however, was as before with the low resolution of the display, which did nothing to reward the close viewing distance of the cramped room. As with so many digital displays, the video disintegrated into jaggy lines and rough textures the closer one approached it. So panning and zooming in there ended up giving me not only a scrambled sensory experience, but also an impoverished visual one.

3d — old

I compare this with old-fashioned stereo photography, which I remember first encountering many years ago, in the 1980s. Visiting the Leroy Street apartment of my friend Jane Nisselson, I happened to pick up a small stereoscope — not an antique, but rather a contemporary mass-produced viewer, molded from black and gray plastic. Peering through it towards the sunlight in her window, I had to force my eyes into a slightly cross-eyed squint, an act that successfully popped the image into startling 3D. There floating just in front of me was a nondescript desk and lamp, an image that possessed an uncanny mental presence.

Jane had been given this stereoscope by Scott Fisher, whom she’d met at MIT’s Architecture Machine Group (Nicholas Negroponte’s pre-Media Lab research center). Scott was to become a well-known proponent of VR, and Jane put me in touch with him when I moved briefly to San Francisco in the early 90s. It was he who introduced me to Michael Girard and Susan Amkraut, whose VR artwork, Menagerie, he had just produced for the Pompidou Center.

Virtual reality never lived up to its exciting promise, and certainly not up to the considerable hype it generated; experiences like the one I had in the Cave proved to be all too typical.

It was years later, in Atlanta, that I crossed my eyes again to peer at vintage stereo photographs. These came from Peter Bahouth’s vast collection, which I had the chance to explore briefly one evening after dinner at his house. First I examined 19th century shots of household interiors, in which I was astonished by the visual detail I could summon forth from the twinned images inserted into the stereoscope. No scene could be taken in at a glance, each too multifarious and detailed for that kind of cursory inspection. But with a little effort, a conscious shift of focus, I could bring the almost palpable presence of a long-vanished object right up in front of me — a vase on a table, a gilt-framed mirror, an embroidered cushion — suspended in space, suspended in time. Each photograph seemed almost infinite, as if I could never examine quite everything it held — I even found myself craning my neck slightly, as if I could see around objects to what lay just behind or beyond them.

Peter then brought out the most unexpected prize of his collection, the stereo photographs a traveling salesman had taken so obsessively at mid-20th-century. There is somethiing about a stereoscope that lends itself to pornography, for not only do the various allurements of the desired body practically shove themselves into your gaze, but also they do so in a space even more private than that of a peep-hole.

None of the salesman’s photographs were explicitly pornographic, though they very nearly were. The one that pinned itself in my memory was of a man and woman dancing, perhaps in a bar. The stereogram caught them just as the man, having lifted his partner, was spinning her around. Her skirt had flared out, and at the apex of the 3D triangle formed by the woman’s momentarily spreadeagled legs was the evident prize: her bright white panties.

For a moment, the stereoscope I held seemed identical to the salesman’s camera, and I had the grotesque sense of his sweaty excitement.

## eye as object

At a recent eye exam, the light the doctor shone in my eye made its capillaries suddenly visible to me, a network of bright red tendrils floating in the darkness of the examination room.

Earlier, the nurse had me peer one-eyed into the scope of a machine, in which I first saw a blurred picture of a brightly colored landscape. The machine whirred slightly as it measured the internal geometry of the eye, and then, without any direction from me, automatically adjusted its lens to snap the picture into focus.

A deserted road receded straight into a bright green landscape, and where the road met the horizon there hovered a large striped air balloon.

inside out

The psychoanalyst-turned-crackpot Wilhelm Reich saw — by the evidence of his own eyes — a constant bombardment of the earth by a life force he called orgone energy. First noticing the telltale bluish light in the darkness of his lab basement, he was soon seeing it everywhere — most obviously in the sky, the color of which he had thus explained. Reich invented the orgone accumulator, a kind of therapeutic isolation box intended to concentrate the play of this life force on its occupant.

Reich’s fancies percolated through mid-century counter-culture, with its antiscientific bias and mystical predilections. That Reich had been imprisoned by the fda only increased his outlaw allure; among the most famous of orgone box enthusiasts was that other outlaw, William Burroughs.

Even the filmmaker Stan Brakhage thought he was seeing orgones when he looked up at the sky, a dance of particles whose motion sometimes seemed to foretell rain. So when as a teenager I gazed out the porthole of an airplane and saw the same particles popping across the bright clouds below, I felt I had joined my heroes.

This was a vision I can still repeat at will. Only years later did I learn that, as with so many miracles, what I was seeing was self-produced: the particles were white blood cells pulsing through the capillaries of my retina.

inner light

In William Burroughs I first read about Brion Gysin’s Dreamachine, a flicker device for hallucinations. Following Gysin’s published instructions, I used a turntable, a light bulb, and a slotted oatmeal box to fashion a dreamachine of my own.

With closed eyes I faced the flickering light, the pattern of which bypassed my retinal vision to induce a kind of direct neocortical vision. This came in the form of huge wheeling expanses of intense and even repellent colors — acid greens, yellows, and pinks — unlike any you’d ever see on earth. The experience pitched me into an odd kind of panic, as if I were on the verge of an epileptic fit, and I did not repeat it often.

flicker-stories

Flicker-track was originally meant to be part one of a long-dreamed-of project to which I’d given the name If by chance. Both the project title and its premise continue to intrigue me, though at the time I was brought to a complete and unexpected impasse — though a highly instructive one.

The project’s original inspiration had come several years earlier as a sudden spark from a book I was reading. (So vivid was it that I can still remember the precise moment: riding the Geary bus, standing-room only as usual, lumbering down the long final hill into downtown San Francisco).

Here’s the exact passage: <div style="margin-left: -25px;width:150px; text-align:right; float:left; font-size:80%; line-height:130%;padding-top:5px; color:#555;"> Actual Minds, Possible Worlds by Jerome Bruner </div> > There is a celebrated monograph, little known outside academic psychology, written a generation ago by the Belgian student of perception, Baron Michotte. By cinematic means, he demonstrated that when objects move with respect to one another within highly limited constrains we see causality. An object moves toward another, makes contact with it, and a second object is seen to move in a compatible direction: we see one object “launching” another. Time-space relations can variously be arranged so that one object can be seen as “dragging” another, or “deflecting” it, and on so on. These are “primitive” perceptions, and they are quite irresistible: we see cause.

I had long been interested in involuntary perceptions — as a teacher I’d encouraged learning disabled children to create and then exchange interpretations of inkblot patterns, which later led to my making the Inkblot Projections kiosk for the Exploratorum. Now I wondered whether one could generate digital animations that would trigger involuntary narratives in each viewer — a kind of story-making machine that would tap directly into subconscious thought.

I had met the curator Larry Rinder who was planning an ambitious show (“Searchlight”) on art and consciousness for the CCA in San Francisco, for which this project seemed to be a perfect fit. And so I began working on it with Shelley Eshkar, even going so far as to create the previsualizations that made their way (most misleadingly) into the Searchlight catalogue.

But as soon as we actually started putting the animations into motion, they became revoltingly anthropomorphic: the little circles and squares automatically assumed antic cartoon personas as if created by Disney or Pixar rather than by — well, whoever we are as artists it’s anyone but that!

It’s not that I turned away completely from the idea, but I was intent on burying it more deeply into the foundation of things. So it keeps resurfacing in subsequent works, but never so nakedly.

In any case, casting the whole notion aside for the moment, I decided to make something completely different & to do so alone. Perhaps in reaction to this experience, I wanted something hard & violent, very different both from the elegant previsualization & from the three dance projects we had just completed.

flicker film dreams

In the back of my mind, I had kept alive an even earlier unfulfilled dream. As a teenager I had been inspired to become an experimental filmmaker more from the books I read than from any actual films I’d yet seen: for even then it was difficult to find such work in theaters. On a spring vacation, then — armed with cement splicer, a hand-cranked viewer, and 2 small Super-8 reels of black and of white leader — I was determined to make a flicker film to match those I’d read about by Tony Conrad and Peter Kubelka.

Hands sticky with cement and eyes like a raccoon’s, I emerged two weeks later with a good 35 seconds of edited film. But when I finally got back to the Bolex projector at boarding school, the film immediately jammed in the gate, its thick, densely-packed splices bursting apart before they could even start their intricate flickering pattern.

When I returned decades later to the idea of a flicker-film, I thought I might add something to this odd tradition using digital tools instead. Of course, while I was now free of cement, I still conducted a decidedly backward effort, especially compared to later collaborations with Marc Downie — for while I had figured out various abstract rules to guide the interactions of my flickering cubes, I then had no choice but to keyframe them painstakingly “by hand” in the 3D program.

The rules, by the way, certainly didn’t give rise to the cute Disney anthropomorphism I was so intent on avoiding: but they did hide the ghost of a story inside somewhere.

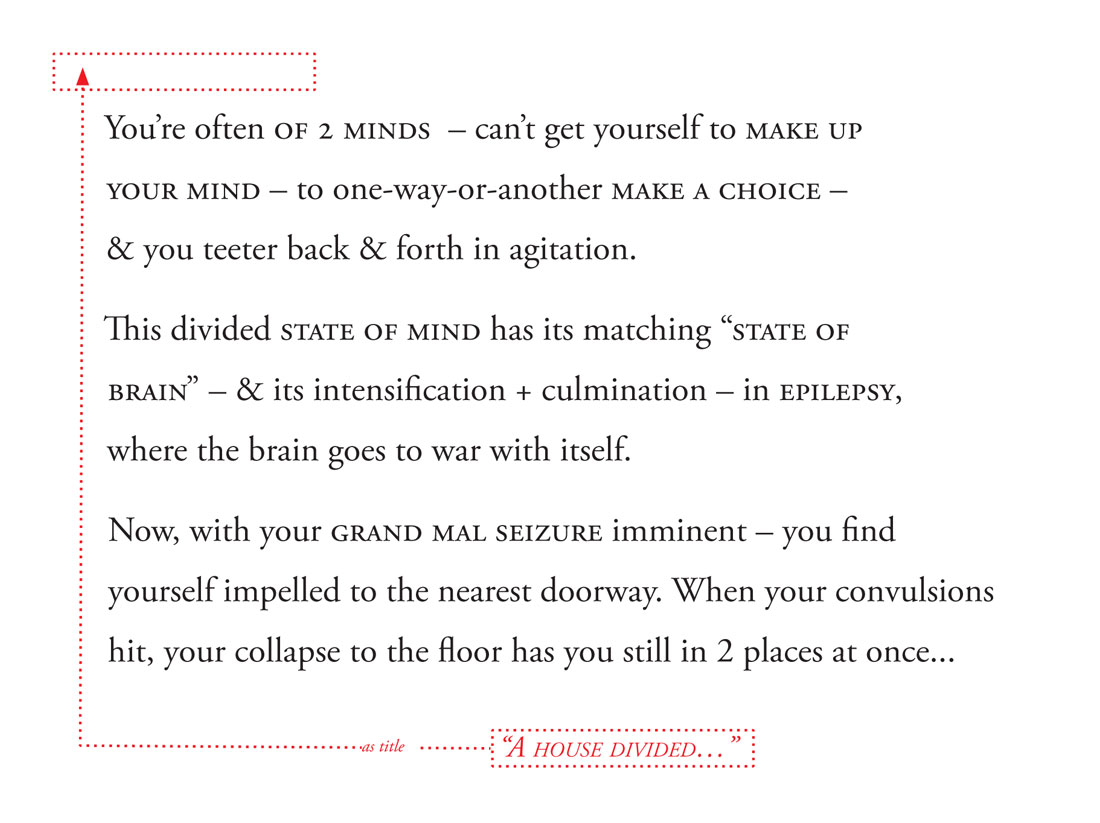

epilepsy

As for violence — the curators posted the usual warning to epileptics outside the door to the gallery first at CCA and later at the Whitney.

As it happened, when I was younger, epilepsy was another of my fascinations, feeling that my kind of nervous dread might somehow put me on the brink of it. I formulated a theory about the “destructive cut,” an act of montage so severe as to plunge you into an epileptic fit.

And so I collected stories about epileptics, one of which has stuck with me even now. It concerns the predilection of some sufferers to stage their attacks in doorways, so that when they collapse, they are not only spiritually but also physically in two places at once. Of two minds.

This turned into a text for Other Bodies:

blind space

When you approach a pitch-black space, how do you know what’s in front of you? For it could be the emptiness of air or the solidity of unseen objects. And so you stretch your hands out in front of you and step cautiously into the space (your feet feeling for unexpected gaps you might fall through).

This is the experience of blind space, the idea that animates Verge, this companion work to Flicker-track.