hitler’s culture capital

The Linz city map, free for the taking at the tourist office, had a plug on its flipside for Linz 2009: Application for European Capital of Culture — “capital” to be understood in both senses of the word, for the aim of such cultural renewals is to bring cash infusions in the form of rebuilding, expanded tourism, etc (Bilbao is perhaps the most successful example of this). It’s the same strategy I’d seen with MASS MoCa’s state-sponsored attempt to resuscitate a moribund mill town, and in fact I was also already familiar with the EU policy of designating cultural capitals. Bruges was one such capital; the city wanted to balance its storied medieval past with a vision of an active electronic future, which led its arts council to project Pedestrian on the cobblestones of the main market square.

So Linz is now making the same kind of pitch, but this has an unfortunately ominous echo to it. For Hitler, too, intended to make his home town the pre-eminent city on the Danube — the cultural capital of the Greater Third Reich, the empire he proclaimed after the 1938 Anschluss brought him to the cheering Austrian crowds of Linz, a triumphal homecoming.

factories

The plane from Frankfurt to Linz puts the peaks of the Tyrol in tantalizing view before it dips down over the city. The curves of the Danube come into view, as does the enormous steel factory on its southern bank, which sends up plumes of smoke. This plant was originally the Hermann-Göring-Werke, named by Hitler after his Luftwaffe commander and right-hand man: an emblem of the industrial renewal that continued to endear Hitler to the citizens of Linz well into the disastrous war.

About a half-hour bus ride east of the city lies another gigantic factory, this one not only dead but sealed off unobtrusively underground — the Mauthausen-Gusen slave labor camp, where in the dying days of the war the Nazis rushed the production of Messerschmidt fighter planes, boasting the first jet engines the world had seen.

audioweg gusen

By far the best artwork I encountered at Ars Electronica in Linz was the lowest tech. This was Christoph Mayer’s The Invisible Camp: Audiowalk Gusen, which consisted only of an IPod and headphones.

On a dismal afternoon of rain and wind, there were only two of us taking the tour. The bus had dropped us off at the small town that was built after the war on the site of the camp, which as a result is little known for its past horrors. The woman’s voice on my headphones started me walking along what used to be the perimeter of the Gusen I site, now lined by neat houses with green grass and nice gardens.

I had worried that the English version of the tour would provide a diminished experience, but it was perfectly done: I could still hear the particularity of the voices underneath giving testimony. These began with the survivors, one of whom remembered the SS telling him that his only way out was as smoke through the chimney. I timed my steps to the ones in my headphone, and so I was at the right intersection when the woman’s voice told me to turn. I headed down a small street, bounded on either side by what had once been a brothel for the guards, an infirmary, and so on — but after just thirty steps or so, I was brought up short by a new No Entry sign: Privat. This, the woman’s voice informed me, had been erected recently by local citizens, blocking the original audiotour route. A telling dead-end, however, for it matched precisely the experience I was having — of the impassable barrier between mundane present and unimaginable past.

The audiotour had me retrace my steps towards another route into the town. The testimonies started to shift from survivors to townspeople, both those alive during the war and those born afterwards. By now the wind had torn my umbrella to shreds and I was soaked. At one point I fumbled for my phone camera and took this meager snapshot of the pavement:

I could see that in finer weather children did play on these streets, as well as in the backyard playgrounds behind many of the fences — and what did they know of those who staggered to their deaths here long before them? What responsibility could they possibly bear? A young man remembered his childhood swims in the nearby quarry, fantastic times cut short when a tour of somber foreign dignitaries came upon these Austrian kids romping in the water — a carefree pleasure thereafter forbidden them. How were they to have known it was an act of sacrilege and desecration?

An old woman recalled her girlhood there — her flirtations with the charming young SS soldiers who were so polite and so engaging. And then of her suddenly encountering one of the horrors they perpetrated: young children tied into burlap sacks and hurled against a brick wall, and she having to step around the blood pooling on the pavement.

I was peering through this orderly village to make out the dim outlines of what had stood there before, my eyes attempting a kind of x-ray time travel. At the back of my mind, I wondered what my gaze felt like to the present-day occupants whom I imagined looking back at me from behind gauze curtains. I stumbled along the route distractedly, but was it only my imagination that the occasional passing car didn’t slow down in the slightest as it overtook me? Maybe even accelerated a bit as it sped past me in the narrow lane?

Another citizen spoke up defiantly over the headphones (a nice place to live, my hometown…). And then started to come the voices of the perpetrators themselves, the old men who were once the young guards there. One the voice of a kind of automaton, saying that he had no guilt, had merely done his duty, followed his orders, had lived a “schizophrenic” existence, now long gone and scarcely remembered.

I crossed a small bridge, which I learned as I crossed it had been built by slave labor. On the other side had been a railroad spur, now just a slightly elevated ridge overgrown with trees, a little muddy path leading into it.

As directed, I made my way along the little ridge, where I was soon enveloped by trees. I came upon a little wooden tower to my left, erected so that deer hunters can train their rifles over the field beyond. In the pouring rain, there was no one there now, and feeling myself finally alone and out of sight, I started crying, overcome by a feeling of utter abandonment.

But the tour continued and took me further. I found myself at the edge of the vast underground factory, where a row of new townhouses had been erected on a little rise. The woman’s voice told me that this was the only part of the former factory that had been filled in, for no sooner had the townhouses been built than they had started to sink and faced the danger of caving in.

The voice of another old SS veteran now took over, unrepentant. His words were to the effect that we could not understand his experience at all, and said that he had tried many times to do so himself so that I am always a step ahead of you, okay? This brought us to the end, where the artwork executes a vivid doubling. As the SS man spoke of a door to memory that we can’t go through together, our footsteps had taken us to the locked gate which is the only remaining sign of the underground factory lying dormant under the green countryside.

pope’s sms

Planted in the grass near the entrance of Gusen I’d seen a large poster bearing the face of the German pope, Benedict XVI. It was raining too hard then for me to dare take out my camera phone, and back in Linz the closest I could find was this:

Benedict was conducting a three-day tour of Austria, trying to rally the mostly lapsed Catholic state back to the church. The poster I spotted at Gusen was part of his marketing campaign: it urged people to get the pope’s word directly via their cellphones.

The placement of the pope’s image in the grassy field by the concentration camp was no doubt accidental, but its presence chilled me nonetheless, given the impassivity of his predecessor Pius XII in the face of the Holocaust. A day later I read that Benedict had just commemorated the Holocaust victims in the old Jewish quarter of Vienna; but then again, there’d also been reports a month or so earlier of Benedict’s having granted a private audience to the Polish priest Tadeusz Rydzyk, whose rabble-rousing radio network fans the seemingly inexhaustible flames of anti-semitism in his homeland.

stadtwanderwege

From the airplane over first Germany and then Austria I’d remarked once again on the European landscape, where you find forests so often adjacent to cities. This I could see was true of Linz as well, for it was surrounded by green hills which I quickly determined to explore.

And so there were pleasanter walks for me than the harrowing one I took in Gusen. The first day I headed off for a hilltop beckoning to me in the distance, twin church steeples on its top. After a game of pedestrian snakes and ladders, in which I was continually brought short by unexpected dead-ends and curving detours, I happened upon a stadtwanderweg sign — “wanderweg” (literally, wander way), a term I remembered fondly from Switzerland, where my wife and I had spent part of our pre-honeymoon traipsing through the network of public trails crisscrossing the nation. Now, in Linz, I could find similar escapes, and the best parts of my days there found me amid trees and the sound of water streaming down the hillsides towards the Danube.

sanctuary for situated reading

The post-industrial landscape of the Canal Robaix brought back strong memories of time I spent in the Ruhr region some seven years ago, which had prompted similar reflections on the repurposing and reclamation of landscape. At the time these thoughts had led to my proposing a very large (but admittedly generic) act of artistic appropriation — the designation of a gigantic steelworks cooling tower as a found object or readymade. Behind this plan was a more interesting idea for creating a sanctuary for situated reading. No doubt too pompous a title, but the notion has grown even more important to me now than it was then.

ruhr landscape

The Ruhr region is of course the old heartland of industrial Germany, where coal mines, steel factories, and heavy industry once flourished. Though very populous, it has no center, but consists instead of a string of cities (Essen, Bochum, Dortmund, and others) scattered roughly from east to west.

What’s fascinating about the Ruhr today is that as its industrial sites have fallen into disuse, the natural landscape has simply been allowed to reassert itself. This has produced an extraordinary terrain in which time seems to have skipped either far back or far forward. Once-mighty factories have fallen into ruin and are everywhere overgrown with vegetation. Even the rivers, formerly noxious, now run nearly clear.

The authorities have designated large tracts of this landscape as parkland, with the old industrial structures turned into climbing walls or playgrounds or cultural centers. Tanzlandschaft Ruhr (“Dance Landscape”) was one such arts organization that grew up in this unusual setting, where it now goes by the name of [PACT Zollverein][1] (the latter part of its name taken from the former colliery where it has its rehearsal, performance, and exhibition spaces).

It was here that Ghostcatching was once exhibited, but what brought me over to explore the whole region was the idea of situating a digital dance installation out in the landscape itself. This was not at first my idea, but was instead the inspiration of the artistic director, Stefan Hilterhaus, whose first step was to invite me over and then put me in the capable hands of Albertus Alhers. Albertus possessed a fantastic knowledge of the whole region, and he could answer any question I posed as we toured the industrial landscape in search of possible sites.

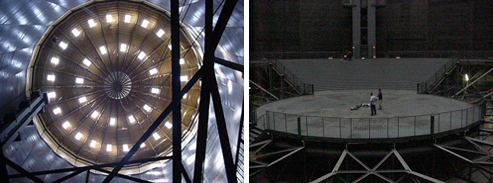

The interior spaces we inspected were often enormous — the largest was the gasometer, pictured above, that was so large as it make a mockery of my camera’s limited viewfinder. Once upon a time its platform rose and fell above the natural gas stored beneath it; but now that platform is fixed to the floor, and as you stand there gazing up at the vast interior volume above, it strikes you as a kind of contemporary cathedral.

This religious association must have struck Albertus somehow, too, for his passion for the Ruhr’s industrial landscapes was exceeded only by his fascination with a monastery somewhere to the north, to which he retreated from time to time as a lay visitor — and where, I later heard, he gave his vows (if that’s how you say it) to become a monk there himself.

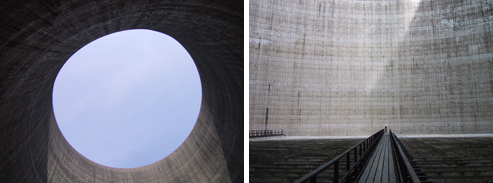

The other interior we explored was that of a gigantic cooling tower that had only recently gone out of use at a steel factory that was being priced out of existence by competitors to the east, in the Ukraine.

Whereas the gasometer was an enclosed space, and thus suitable for the huge projections we later proposed for it, the cooling tower was open to the sky. It dwarfed you, but your thoughts rose upward in a curiously transcendent fashion — somehow your mental space seemed to expand as your own physical presence diminished.

Albertus informed me that under German law industrial buildings of this size had to be dismantled after two years of disuse — a term that was rapidly approaching for this tower. As we stood there contemplating this wasteful necessity, it occurred to me that the owners could save themselves this vast expense by having an artist redesignate it as an art object.

As an artistic act, this was far from original, and it also had nothing to do with my own artistic process or inclinations (better suited to someone like [James Turrell][3]). Nonetheless, working afterwards with Shelley Eshkar and Marco Steinberg, I proposed the simplest of interventions: a wooden bench running around the full interior circumference of the space and a minimal set of lights to permit its use at night, perhaps for performances or simply to take in the night sky.

situated reading

But what really interested me was to make this into a site for situated reading, as I later came to call the idea. I imagined having several sorts of short allusive texts, printed exquisitely on small hand-outs, that visitors could read while sitting in that vast space and then take home afterwards for further reflection.

These were to frame the site differently, so that one text might place it in a cosmological framework (as a kind of readymade Stonehenge) while another (perhaps commissioned from the German writer WG Sebald [this was before his fatal car crash]) would recall its specific history, and in particular the tremendous violence now silenced there — the Allied bombers overhead that once reduced the whole region to rubble in the latter stages of World War Two, and the contentious events (the Versailles Treaty, Hitler’s reoccupation of the Rhineland, the Nazi armament industry, etc) that had brought them there.

##countryside questioned

The astonishingly efficient Train de Très Grand Vitesse, which whisked me from Charles de Gaulle airport to Lille in just over an hour, reminded me again of what I’d observed last month over Germany and Austria — how quickly in Europe the urban landscape gives way to countryside.

My railway passage north was through a ragged fog which had been much thicker a bit earlier, on my arrival: I had thought us still descending through the clouds over Paris when our wheels hit the runway with an unnerving jolt. Now the blurred landscape spooling by the train window was of wide farm fields bounded by stands of trees and the occasional stream, with flocks of sheep here and there in the distance.

But even when farmland yielded entirely to forest, you would never mistake this kind of countryside for wilderness. Everywhere it bears the imprint of long cultivation, of continuous habitation over the course of many generations, which endowed the land with its pleasingly human scale.

And so this cultivated countryside is gentle on the eye even as it rushes past, a welcome respite for the soul — for the French soul in particular, for here the land is still said to exert a strong emotional pull.

The power of this allegiance, however, is exacted politically, the French farmer staunchly defending his land and his way of life by means of high governmental subsidies and even higher trade barriers. So that the landscape you enjoy here comes at a heavy price elsewhere — in Africa, for example, whose farmers suffer from the markets (and mouths) closed off to them to their north.

This kind of perspective clouds our visual view of the land, and rightly so, for what your eyes cannot see is often truer than what they can.

quicksand

These reflections put me in mind of Fred Camper, who was my mentor and guide for the best part of the 1970s. A film critic (and, at that time, filmmaker), Fred’s unparalleled devotion to film was belied by the same kind of fundamental doubt about what is given by the world to the eye.

This, as he once explained to me in a long letter, came from a fundamental revelation of his childhood, triggered by his realization that the beautiful blue of water seen in the distance did not signify its purity — that all the water surrounding his island of Manhattan was in fact grossly polluted. Oh, he explained all this much more eloquently than I can remember, but his point was a kind of existential grief over the fact that what he saw was so much at odds with what he might touch or even taste (should he dare).

Only in true wilderness, he said, were the senses not betrayed by each other like this, and so when he could afford it he would arrange to be dropped by small pontoon plane in the wilds of Canada, where he would spend a week or two hiking back to civilization.

On a bookshelf in my studio I still keep a prized box marked Camper correspondence, which for some reason I have not perused in scores of years. But in that box there exists the forty-or-so-page letter that Fred wrote to me over the course of the longest (and perhaps even the last) of his wilderness trips. I remember that when I opened this letter I immediately noticed that its pages were oddly smeared and stained. The reason for this became apparent about two-thirds of the way through Fred’s chronicle, on a page written just after he’d extricated himself from a patch of quicksand that had briefly threatened to swallow his body and backpack whole.

Had an overhanging branch not been within reach… — but it had been.

And so survived his most dramatic proof of the unreliability of sight.

##landscape repurposed

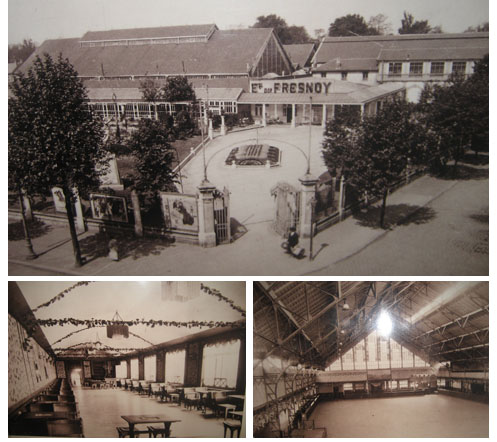

«Le Fresnoy – Studio National» is an unusual institution plunked down just south of Lille in the north of France — a post-industrial landscape of abandoned factories, boarded-up warehouses, and disused canals, where the old small-town life is still lived out on old streets and houses, with old shops, schools, and graveyards interspersed among them. Busy highways and efficient mass transit (trams, trains, and metro) hold out promise for its future, as does the presence of the many immigrants who have found refuge among the ruins, provided they can all find jobs somehow within the rigid French economy.

Physically Le Fresnoy looks to be another cultural reclamation project, with the original building on the site now partially reclad, in familiar postmodernist style, in an ironwork exoskeleton of ramps, catwalks, spiral staircases, and roof extensions.

My first impression was of a factory repurposed, but this proved wrong. In fact the place was once part of a grand amusement park, built during the Depression and shuttered several decades later. The present exhibition, cinema, and post-production spaces were once given over to indoor roller rink, amusement arcade, dance and dining halls, and the like, as I could see for myself in a few old photographs:

The «espace d’artist» where I was put up proved to be a most eccentric living quarters. I opened the door to a small dining-room/kitchen with enormous windows reaching way up above. A spiral staircase took me the long way up to bath and bedroom overhead, where small windows gave on a view of the eaves and catwalks of the elaborate roof structure. But I was drawn back down the staircase to the large windows again, where I gazed out past the busy highway right below to the small canal running through a woods just beyond it.

canal robaix

My first four days were filled with work, and I was able to venture out onto the canal towpath only briefly and always in the persistent fog so characteristic of the Lowlands. But the weekend was my own, and since the fog now gave way to bright blue skies, I decided to explore the Canal Robaix fully.

On Saturday I followed it southeast for four and half hours until it reached the River Duelle which in turn took me down into Lille proper; on Sunday I traced it north for two hours till I imagined myself to be at the Belgium border, though there was no sign to tell me so, such is the present trusting state of the European Union.

The canal no longer seems to function commercially, though its many locks are in good working order and the water itself free of debris (not, however, of pollution). There are barges to be seen from time to time, but these are all moored in what looks to be a near-permanent state. Two boys I saw had the right idea about them. Having boarded one, they were busy peering down into its hold and imagining an alternate existence for themselves, new lives lived along the water in long-departed past.

The canal is still by used fishermen, who line certain banks singly and in bunches, sticking their exceptionally long fishing poles way out over the water. On neither of my long walks did I see any evidence of any catch — a good thing, for with the frequent smell and sight of effluent pouring into the canal, I held out hope for the continued futility of their pursuit, with which they seemed content enough anyway.

In some places, a thick green scum carpeted the water. So thick did this seem that one time I thought I saw ducks somehow standing upright on top of it, though actually they were perched on a branch suspended in the green growth.

So it’s an odd kind of nature that persists in and along the canal. Wherever there’s a chance, though, the urban element imposes itself via spray-paint. Graffiti springs up at the earliest sign of desertion, so that even on a seemingly ordinary street of houses I was surprised to see one house, garden still flourishing, painted over with the same universal tags I’d seen on bridge pylons and underpasses. Other than the graffiti, a single broken window was the only sign of the house’s abandonment.

There are other acts of repurposing the landscape, applying a different kind of label to it. Towards Lille, I came across a model farm on the banks of the canal, with chickens and horses and vegetable gardens and an old stone farm-house complete with courtyard (and retrofitted with a small cafe). This was a working farm, but its work was educational: built for school groups and family outings, it provided a kind of sign-posted demo of a way of living now long gone.

I forgot to snap a picture of it, though your generic mental image will do just fine.

##second language

At Le Fresnoy I have found myself immersed in a sea of French discourse, the waves of which mostly splash right through my outstretched hands. My attempts to speak the language have been equally sorry, try as I might to draw on a dimly remembered high school vocabulary never large to begin with.

I tell my Garden-of-Eden / Fall-from-Innocence story in the “Belgrade”section of Trace. This may (or may not) explain my ineptitude with foreign tongues, a shortcoming I share with most native-born Americans though not with three members of my own family, each of them fluent at various times in multiple languages (my father in seven, my mother in five, my brother in four).

baby steps

At the heart of my present difficulty is that I balk at reverting to that state of near-infancy demanded of you as you make your first teetering steps in an unfamiliar tongue. I can’t bear hearing my thoughts come out in such a faltering and babyish fashion — a sin of vanity, I suppose.

But if I hate to be childish among adults, among children it’s a different story — which made speaking French much easier on two isolated occasions a long time ago. There was the week I stayed with a wonderful family in Jouy-en-Jousas, whose toddler conversed with me freely, and I equally so with her, since we were both more or less on the same joyful level.

And then there was the earlier time in the Laurentian mountains of Quebec, where I was honorably inducted into a small troop of Québécois youngsters, whose backwoods French sounded deliciously rough even to my untrained ear. I remember that during a lively game of hide and seek, one little girl kept repeating the word «bouaze » to me, stressing the s/z sound that is omitted in the “proper” pronunciation of the French word «bois».

Only when she pointed to the trees did I understand she meant the forest nearby — and then I acted on her suggestion immediately, dashing into that «bouaze» to hide behind a big old tree whose roots I now picture pushing deep into the rich loamy soil of colonial and even of pre-colonial times.

code-switching

It was by chance that I had found myself in the Laurentians, a spur-of-the-moment side-trip following my brother’s wedding the week before in nearby Montreal. My new sister-in-law, now ex-, Monica Heller, was a brilliant sociolinguist then writing her doctoral thesis on French/English relations as observed over the course of her fieldwork at the Molson beer factory there. A particularly telling linguistic move, which she tracked and analyzed carefully, was that of code-switching — that is, when an interlocutor suddenly switches in mid-conversation from one language to another .

How ironic, then, that code-switching later played a role in the attitudes of her two children, my beloved niece and nephew, towards the Old World in general and towards the City of Light in particular. Having grown up completely bilingual, their hopes for Paris were dashed when the Parisians they met there were evidently so offended by their barbaric Canadian accents that they would code-switch on them derisively, shifting from fluent Parisian French to broken but condescending English.

lingua franca

In the aftermath of World War II it was code-switching on a global scale as American soldiers, bureaucrats, businessmen, and tourists fanned out across the world, turning American English into the second language of most countries, and certainly of those of western Europe.

Here, however, the situation was not purely the consequence of the Marshall Plan, cultural imperialism, etc, etc. — for Europeans themselves seized upon English as a neutral tongue with which to communicate across their borders, thus avoiding the strife that would have arisen had any one country (e.g., France or Germany) tried elevating its own tongue to the status of lingua franca.

Significantly, the accent the Europeans chose to learn and use was not the one across the Channel — never England! — but the one across the Atlantic.

high-mindededness

This linguistic situation accounts for the odd role thrust upon me in conversations at places like these. Rather than being infantalized as I struggle to speak in a foreign language, it’s quite the opposite in this realm of international English.

Here I find myself widening my eyes, broadening my smile, amplifying my gestures, and of course exaggerating my enunciation — a parent addressing a child.

This is obviously truest when my interlocutor’s command of English is uncertain, but it’s still subtly the case even when he or she is perfectly fluent. The language we instinctively adopt is still slightly simplified, as are our expressions and even our emotions.

What emerges is a high-minded, Family-of-Man idealism in which we are all at pains to underline our common humanity and lofty aspirations, kind of like kindergarten circle-time, a tone very different from, say, a typical New York City exchange.

low life too

American English connotes low-mindedness too, if there were such a word — a sense of the low life and the down and dirty. Or at least of these stereotypes.

This can lead to poignantly ludicrous situations in which Europeans rely on English both as lingua franca and as rebellious expression. Some years ago I sat with William Forsythe in what was then the grand hall of his Frankfurt Ballett, where we were watching a renowned Flemish dance troupe perform their latest and unendurably long work of dance-theater. It was sad enough that the Flemings felt compelled to deliver their lines not in their native tongue, nor even in the German to which it is a close cousin, but rather in English. However, what made this spectacle — that is, the spectacle they made of themselves — so truly sad to me was their expressing their edgy world-weariness in poorly accented American slang punctuated by the occasional harsh obscenity. Unintended quotation marks hovered over their every exclamation, and gave the lie to any sincerity that may once have sparked the would-be spirit of the piece.

global argot

It’s not just the words and phrases of exported American English that took such odd root in Europe and elsewhere, but also its visual language.

In the bitter campaigns of World War II, American grunts had marked their unexpected presence on foreign land with their wryly anonymous Kilroy was here. Afterwards, though, it was European kids who started tagging the continent themselves as if it were Harlem, the Bronx, or Bedford-Stuy. Their spray-painted scrawls were indistinguishable from those across the sea (so much for regional difference).

Even American political graffiti made its way over into this odd cultural irrelevance. Aarhus, Denmark, must be one of the blondest cities on the planet, but I remember encountering down near its waterfront a spray-painted Free Mumia slogan executed in identical fashion to those seen in the States a years before. Meaningless solidarity, empty gestures…

Such borrowed attitudes are often worn on one’s sleeve, as it were — as clothing.

On a Friday night last month in Linz I saw a troop of young teenage boys, each wearing huge baggy pants that sagged well below their unbelted waists. To be fair, in this they were no different from their us suburban counterparts. It was as if milk-fed boys the world over long for a more desperate and edgy world — one in which their black fathers and uncles have brought home from prison not only a flair for wearing ill-fitted state-issue clothes but also a disdain for belts prohibited there as possible instruments of suicide or escape.

visages

Visage is one of those Norman words that to my ear never succeeded in embedding itself snugly in English, or at least in American English. At least when I pronounce it in the correctly Anglicized fashion [viz ij], the last syllable seems clipped too tight for me and I picture myself instead as an English colonel, a well-trimmed mustache on my stiff upper lip.

My contemporaries and I tend to pronounce visage in the French way [viz ahje] — and do so ironically, with raised eyebrows and in implicit quotation.

Visage is absolutely the mot juste for certain eminent faces I saw on my first evening at Le Fresnoy. This was in the lovely cinema there, where Allain Fleischer, who founded and now runs the place, was premiering a documentary. The film consisted of interlocutions with Jean-Luc Goddard, the filmmaker married to his label enfant terrible (auto-prepended now by aging).

The faces of all the interlocutors, several of them now also present in the flesh at the front of the cinema, were indeed magnificent visages. They cut a profile as sharp as Voltaire’s, and I could almost imagine myself back in an earlier time of declaratory eloquence.

My limited French kept me from following the lively interchanges both on screen and, afterwards, off — but I couldn’t fail to remark on the fluency and unstoppable flow of phrases, nor to observe the tremendous pleasure these older men (for no woman was among them) took in their discourse.

After the film, this fluency was interrupted only by cantankerous outbursts from the back of the cinema, where a cigar-chomping old fellow bellowed at the men in front. He turned out to be the irascible director Jean-Marie Straub, who seemed himself to have stepped out of the pages of a 19th century novel, perhaps by Zola. His harsh remarks were gently returned, and even this spirited debate seemed part of an old and even courtly ritual of vehemence.

talk shows

I couldn’t help but think of the contrast with public figures in America, where even artists tend to present themselves to their audiences with the casual flip cleverness of a guest on the Johnny Carson (or now David Letterman) show.

My thoughts then turned to my dear departed aunt Doris, who had been the most devoted of Francophiles. She would tune in the television to Bernard Pivot’s talk show «Apostophes», where literary types would hold forth in precisely the same way I saw at Le Fresnoy. For Doris, this French exposure helped her endure the long months of fall, winter, and spring that kept her in Manhattan rather than in the beloved Provence of summertime (admittedly a world apart from the industrial landscape of Lille).