strange mindfellows

Toward the end of his life, Paul Valéry noted that others kept wanting to claim his thought for Buddhism or for Theosophy, systems he knew nothing about. He went on to observe that

people who “think” move around blindfold amid the tiny room of the human mind — and in this metaphysical game of blind man’s bluff, they bump into each other — and push each other away simply because they’re moving about, and the space is very restricted. It’s the space of a dozen *words*.

Emphasis added, partly to underline Valéry’s sounding so unexpectedly like Wittgenstein — another strange mindfellow whom we can add to the list.

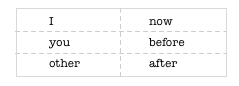

But the first list to compile would be a stab at the dozen words Valery had in mind — even though I doubt it was an exact number: a dozen is simply more than a handful, which would have been easier. We might begin

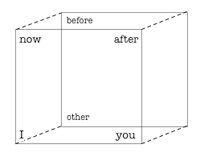

And once we’d completed such a list to our satisfaction, we’d next have to take a stab at diagramming the space these words form, since that’s the apparently cramped room in which all these mindfellows bump heads.

How appropriate that my botched sketch of such a space would produce a Necker Cube, an optical illusion that keeps keeping flipping foreground and background, mind oscillating between two opposite readings — an unwittingly accurate portrayal of my own mental space, if not yours.

But for now I’m interested in who it is that’s crowded into there — philosophers, gurus, dreamers, poets, spiritualists, psychologists, etc.

Or not even that: I want to know the effect of all that crowding.

tumult

One effect, surely, is that of contamination. Different thinkers impinge on each other, subtle discriminations blur out, buzzwords proliferate, and after a while there’s even a sense that all these disembodied presences are battling for your mind-share.

Descartes argues with Dogen who’s fending off Whitman, but their disputes quickly get so entangled that you can no longer tell where one begins and the other ends. Add to this a bit of incense and sitar music, a dash of psychedelia, some crackpot particle physics Taoism, both the Egyptian and the Tibetan Books of the Dead, etc, and before you know it your mind is buzzing in confusion.

In place of the quietude you’d sought in your inward reflections, what you encounter instead, at least at first, is a kind of seance run amok, all the spirits clamoring for your attention.

For you are the medium through which they must either pass or perish, a thought that puts me in mind not only of Richard Dawkins and his notion of memes, but also of Philip K. Dick.

jory

In Ubik, Dick imagined a cryonic facility that can prolong consciousness past the point of death. Once there, any disembodied half-life is gradually used up in communications with others, who must therefore keep their message-passing to a minimum.

Soon the protagonist discovers not only that his friends and associates are all suspended in this limbo, but that so is he. To make matters worse, an energetically degenerate adolescent named Jory is also in there, and he’s busy eating up everyone else’s bodies of thought, taking over all mind-share.

Imagine a teenage neighbor who keeps turning up the volume of his music to drown out yours.

—It’s a noisy world that keeps consuming my thoughts no matter how inward.

##mother : fetus :: writer : reader

mother : fetus

Baby cradled in mother’s womb — no picture tells more compellingly of close harmony between beings.

There’s no doubting its truth, either. But truth is various, you know, and medical science now paints the scene from a different perspective.

Now we learn that in addition to love and bonding the mother and fetus compete for available nutrients, an unconscious tug of war as each tries to gain the advantage over the other. This is sometimes to the fetus’s detriment (which can be as extreme as spontaneous abortion), and sometimes to the mother’s (whose insulin resistance, manipulated by fetal hormones, may lead to perilously high blood sugar level).

writer : reader

Writer cradles reader in the ecstasy of a great book…

— but this harmonious picture can also yield for a moment to a similar change of perspective, for the interests of writer and reader may diverge as often as they coincide, the two locked in a struggle over the scant resources of time and attention.

The writer is especially intent on so captivating the reader as to delay his or her pell-mell rush through the pages, the devouring in seconds of passages that took hours, days, or weeks to compose and whose full meaning can only unfold in a reflective and expansive time at least as long as the time of their writing. Thus all the stylistic tricks by which writers try seducing or commanding their readers into submission, keeping them within the margins of their book.

intercourse

This brings to mind the erotic struggle of intercourse, in which the profound harmony of lovemaking may also veil a similar pitting of delay and prolongation against headlong rush and climax.

if a lion could speak

Wittgenstein was right in a great many ways, but certainly wrong (it seems to me) in one.

When he remarked that if a lion could speak, we would not understand him, he was mistaken.

After all, wouldn’t we get Wittgenstein’s lion perfectly well if he were to exclaim hungry! or horny! or cold!?

Surely there are a good number of elemental things that he and I (and you) all feel in the same fundamental way — sleepy, irritated, sated, snug, itchy, sore, for example. And even torn, unsettled, fresh, perplexed, secure, etc.

Those are all states of mind/body, and as such pretty simple to designate: a single word does the trick.

But what about stringing a number of words together in a sentence? Well,

I’ve just eaten so I’m full and feel like lying down over there on that warm grassy patch in the sun

wouldn’t be beyond the reach of our mutual understanding.

translation

This all works for one main reason. I can translate the lion’s thinking to mine because I can translate my body to his.

The lion and I, each of us a mammal living on the planet Earth, have quite a few things in common: a heart, a spine — a pair of lungs, of eyes — nose, mouth, teeth, tongue — throat, stomach, gut, anus.

We each have four limbs, and if all of his are legs while two of mine are arms, still, I know from crawling what it’s like to be down on all fours. It’s true that I can only crawl clumsily, but still, I can imagine doing so superbly — spine parallel to the ground, lungs filling with air, heart beating, eyes alert, ears perked, tail twitching.

I can think my way from this body to that.

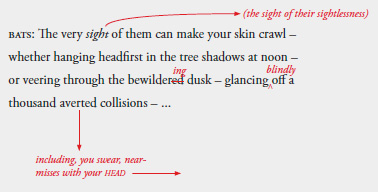

bats

Much harder to think my way into bodies that have, for example, a very different relation to gravity, on the one hand, and to the sensory world, on the other — as this text from Other Bodies suggests.

Also hard to imagine the thoughts and sensations of an electric eel — or (as Marc suggests) any eusocial animal, like an ant or a termite.

woman

One last thought about Wittgenstein’s remark.

If it were true, you know, then when a woman speaks to me, I wouldn’t get her either.

##voicing

Just as by law all non-French films must be voiced over before being projected in French cinemas, so too must all foreign programs be dubbed before being broadcast on television. Though the government also limits the proportion of such shows, you do come across a fair number of them as you idly change channels — Law and Order and CSI Miami rendered peculiarly disembodied by the robust French voicings and the mismatched lip syncs.

Only once have I had the reverse experience, back in the 70s when I saw Chabrol’s «Le Boucher» dubbed into hearty American English, a distraction that destroyed my viewing of it. How lucky that in the US foreign films are subtitled rather than dubbed. The quiet of Bresson and Mizoguchi is heightened by the act of silent reading with which we translate the music of their unfamiliar tongues.

polish dubbing

All this was brought to mind during a trans-Atlantic flight back to New York, when my eye was caught by a headline in the European edition of the Wall Street Journal: On Polish TV, familiar voices. Viewers like dialogue done deep and flat; husky ‘Housewives.’

The article went on to say that

American shows aren’t dubbed by actors mimicking the original, English-speaking actors. A lektor, the Polish term for voiceover artists, reads all the dialogue in Polish. Viewers hear the original English soundtrack faintly in the background. ¶ The approach is popular in Poland, where viewers still feel comfortable with a style deeply rooted in the country’s communist past. Lektors, traditionally men with husky voices, pride themselves on their utterly emotionless delivery, their craft honed through thousands of hours in recording studios. Fans appreciate the quality of voices, often tempered by years of cigarette smoking.

A better solution to the problem of voice-overs, unwittingly Brechtian.

bucharest

This article in turn took me back to my time in Bucharest, where I lived for a year after college. There I devoted myself to writing pieces for my tape-recorded voice, a long effort that yielded only one decent result, a 20-minute composition called Thoughts on erasing blank tape, a few fragments of which later re-emerged in Trace.

It was oddly appropriate, then, that by some odd circumstance I was pressed into service as a voice-over actor for a mamaliga western («mamaliga» being the Romanian national dish of polenta). With me were three other Americans — the Air Force attaché and two Marine corporals serving in the embassy guard.

A mini-bus took us to the cramped movie studio, where the director, speaking through a translator, explained the gist of the film: Romanian cowboys emigrate to the Wild West.

My character was an American cowboy whose edgy rashness was to end his life almost immediately. I stood at the microphone watching the looped projection of my double, who reclined in a barber’s chair, his face covered with a huge lather of white shaving cream. In the facing mirror he spotted his Romanian adversary entering the barber-shop, upon which I was to deliver my two lines of American insult. These triggered my —or rather his — immediate death in the next shot (so to speak).

Little did the Romanian director or his eventual viewers realize that this cowboy’s accent was a far cry from John Wayne’s. No, it was with a diffident prep-school accent that my voice performed its odd imposture.

## of names & nations

One of my best friends made a good impression on me long before I ever met her, simply by virtue of her name — Jane Moss. I had heard mutual friends mention the name from time to time, and to my eyes and ears, the words — so symmetric and balanced — radiated clarity and strength: as did she, I was soon to discover. (I have no superstitions about the power of naming, of course; would never dispute Shakespeare’s a rose by any other name…)

But I was reminded of this recently when Jane and I met for brunch. In the course of our conversation, she happened to tell me of a new Austrian friend of hers, mentioning in particular a curious remark of his: that one’s happiness starts with loving both your name and your nation.

This was puzzling because his nation has been little loved this past century or so, at least by its foremost writers and its many emigrés; but then I gathered that it was the land itself he loved — its mountains, rivers, trees, and light — which made perfect sense.

Another curiosity was that the given name he found so congenial, bestowed upon him by his father, linked him quite distinctively not to his homeland at all, but rather to another country, well to the north.

A paradoxical little story, but less so than two others.

peretz → perec

A few weeks earlier, I’d been reading George Perec’s oddly paired memoir/fable of the Holocaust: W, or the Memory of Childhood.

On page 36 Perec explains how his surname, a strange spelling for French, might have come about:

An official hearing in Russian and writing in Polish, it has been explained to me, will hear Peretz and write Perec. But it is not impossible that the opposite is also true: according to my aunt, the Russians are supposed to be the ones who wrote “t”, and it was the Poles who wrote “c”. This explanation signals but by no means exhausts the complex fantasies, connected to the concealment of my Jewish background through my patronym, which I elaborated around the name I bear, a name which is distinguished, moreover, by a minute discrepancy between the way it is spelled and the way it is pronounced in French: it should be written Pérec or Perrec (and that’s how it always is written spontaneously, either with an acute accent or with a double “r”); but it is Perec, despite the fact that it is not pronounced Peurec.

Perec’s father died on the front in the early days of the Nazi blitzkrieg. Two years later Perec’s mother was sent to Auschwitz (“she saw the country of her birth again before dying”). However, she’d already taken the precaution of sending her only child off to the country, where it’s possible that his un-Jewish name on the roster of Catholic schoolchildren saved him from the same end.

If (as seems likely) this thought ever occurred to Perec, then perhaps his lifelong fascination with the workings of chance owed something to this quirk of fate.

chasis → kaiser

Stranger, if I were to present my US passport to you, it would give my name as Paul Allen Kaiser and place of birth Munich Germany. The features in the passport photo would do nothing to contradict your logical inference that I’m of German origin.

However:

Kaise had once been Chasis: the guttural phoneme ch of the original Yiddish had been switched at Ellis Island to its nearest English equivalent: k. And then the rest of the name kaiser must have been pulled out of the air to match the fresh immigrant start of that new_k_.

As for Munich, I was indeed born there, but not on German soil, technically. No, I spent a week in a US Army hospital before returning with my parents to Belgrade, where my father served as a diplomat in the embassy.

Belgrade became the site of considerable linguistic confusion as well, but of a different sort. I’ve pictured it in the “Belgrade” section of Trace.

paul → paula

My occasional passage from male to female occurs when the printout of an airline boarding pass crams my middle initial against my first name, making me a paula rather than a paul. This is much to the consternation of the flight attendants as they seek to deliver my “special request meal” — vegetarian, not kosher.

not by any other name

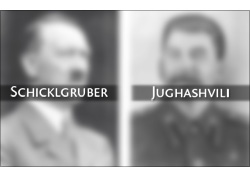

— responding to these thoughts, Fred Camper remarked that if only there’d been a law against changing your name, the 20th century would have been immeasurably better. Hitler would have remained Schicklgruber, and Stalin Jughashvili.

We would never have heard of either of them.

##all about me

One night at the dinner table my oldest daughter performed a short but pitch-perfect impersonation of her voluble English teacher. Looking around at us earnestly over make-believe eyeglasses, she said, OK, class, let’s talk about me.

precocious social engineering

A year or so later the story came home of a different English teacher, whose 7th grade students had feigned interest in her home life in order to extract from her the name of her dog. As they’d guessed, this proved to be her computer password, and so in the few days before their whispered boasting gave them away (Guess what I can do?), they had free run of the school’s network, filching tests, altering scores, peering in personnel files, etc.

password

I’ve often thought that a close unpacking of the passwords you’ve chosen over the years would form a succinct and essential autobiography. Such an account would delve not only into the surprisingly limited number of personal associations you repeatedly draw upon (pet name, birthdate, favorite whimsical word, and the like), but also into the equally restricted number of strategies you employ to disguise those associations (substituting numbers for letters, transposing keystrokes, etc).

I would try recovering and recounting my own password history for you here by way of example, but shouldn’t run the risk of compromising my identity.