locating world war two

Until last week I assumed that Chicago’s Midway Airport derived its name from the idea of its being a midway point between the two coasts. Since the gates to my flights had never been on Concourse A, I hadn’t encountered the memorial to the Battle of Midway there, which gave a completely different explanation.

I had three reasons to stop and study the memorial carefully. First was simply the strange incongruity of an airport exhibit devoted largely to air war of the deadliest kind. Second was a wider interest in the Pacific Theater (so-called) of World War II, triggered the week before by my father’s reminiscences and reconstructions. And finally a professional interest in airport displays, taken ever since we embarked on creating one ourselves Horizon.

The memorial is in several parts, with a dive-bomber suspended from the ceiling the first to arrest your attention. It looks remarkably small, its toylike appearance heightened by the printed transparency behind it, which depicts an accompanying squadron in flight and resembles the backlit backdrops of the miniature dioramas you’d see in a natural history museum.

On the wall to the left of the dive-bomber is a series of three video panels, with buttons that let you play back short snippets of battle strategy and archive footage, and also illustrated explanations of its connection to Chicago — in particular to Lake Michigan.

For it turns out that many of the Navy aviators got their training on the Great Lakes, and some of the planes ended up crashing there. When a salvage company dredged up the now-valuable relics, I was fascinated to learn, they restored the planes for exhibition — as they had for the one hanging over me. But could I have read the signage properly? It was hard to believe that the shiny airplane overhead could ever have lain at the bottom of the lake. But then, the artifacts of death and war are all too often rendered unreal.

A further case in point was the memorial’s main exhibit, which I’d strode right past without its having registered fully. When I turned back to inspect it, it proved to be a large metallic chamber with inspirational quotes on the outside and vaguely 3d murals on the inside. These, I read, were

PhsColograms, a process of digitally combining black and white and color images with computered generated models and outputting these composites as 3d hard copies.

The visual and sentimental effect of this is kitsch, a kind of sentimental throwback to the patriotic TimeLife book illustrations I remember from my childhood. A far remove from the death and destruction visited not only on the decisively defeated Japanese armada, but also on the US forces — whole squadrons flew off to their complete annihilation over the Pacific.

Almost out of view, the designers provided a little key to their illustrations, identifying each of the elements — faces, types of aircraft, opposing carriers and battleships, and so on. I wish I’d studied this key more carefully, for it’s only now as I peer at the image above that I realize that figure to the left there — himself peering through what appears to be a 16mm camera — must be the great filmmaker John Ford. Well, great filmmaker, though perhaps not on that occasion. He was bravely on hand to capture the Japanese air attack on Midway in riveting hand-held footage, but the 18 minute film he then fashioned was pure propaganda, with its own fair share of kitsch: folksy voicings by Henry Fonda, uplifting martial music, taunting jokes about the Japs, etc.

That day in Chicago, it had been a heavy snowstorm that had delayed my flight and given me the time to examine and ponder all this. When our regional plane eventually took off through the pelting snow, its little aluminum body shuddered through the updrafts and air pockets, making me wonder with an odd detachment whether a wing might tear off, sending us hurtling down into the drink below…

My thoughts turned to my father.

scope

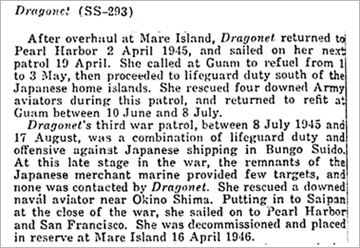

In 1945, off the coast of Japan, US submarines on lifeguard duty would surface to rescue downed pilots — a materialization nothing short of miraculous (I imagine) for the dazed airmen floating there helplessly in their life-vests.

My father served two tours of duty on one such submarine, the SS Dragonet, where he was an Electronic Technician Mate — a fact I’ve always had a hard time crediting since he proved to be so cheerfully incompetent in any and all technical matters thereafter. His was a textbook case of learned helplessness, but as such it was simply an extreme manifestation of his general act of forgetting the war (or rather, his war).

With the rise of the Internet, however, veterans could now find each other all over the map. Old shipmates, last seen six decades earlier, used first Google and then email and phone to contact my father, who before long was exchanging information and recollections with them.

They had more to go on than their memories, however, for the Internet also brought access to declassified wartime documents, including the Dragonet’s patrol logs. Such records sometimes gave new precision to their reconstructions, though they soon noticed that the logs were heavily redacted (why need they be, so long after the fact?)

Missing from the record, for example, was a moment they’d never forget. My father had been asleep in his hot bunk alongside the forward torpedo when suddenly he heard and felt the hull being struck by a fusillade of bullets. The sub dove swiftly to elude a strafing Japanese fighter, the men later cursing the stupidity of the nonchalant officer who’d been supervising the look-out in the conning tower.

Also missing from the log is an eery occurrence three days after Japan’s surrender. The Dragonet had surfaced and was steaming home triumphantly when a torpedo suddenly churned across its path — the narrowest of misses.

That much my father remembered. But missing from his memory was what his old shipmates now told him: that he had been the lookout who’d spotted the torpedo’s wake and given the crucial warning to divert course.

Such events were matters of life and death, but the number of souls involved were few — compared to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The crew were almost immediately aware that devastating new bombs had been dropped on Japan, quickly ending the war, and they realized that their boat could not have been too far away from them. Some of them recalled the strange long-lasting vibration in the water after the Hiroshima attack.

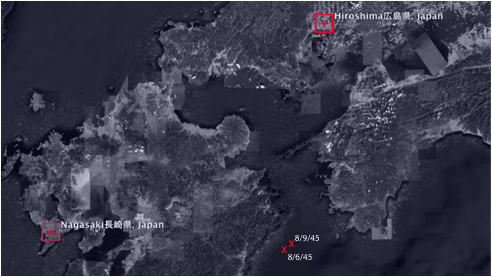

But now the declassified patrol log gave them their exact location on both days, which my brother-in-law tracked in Google. This put them roughly ninety miles away from both blasts.

Thus this view of the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima, taken one hour afterwards from a US plane over the Seto Inland Sea, was at about the same angle as theirs would have been had they surfaced.

They had been ordered into the area, they figured at the time, to fish any stricken B-29 airmen from the sea.

Neither the crew delivering the deadly Little Boy to Hiroshima nor the one conveying the Fat Man to Nagasaki had any need of rescue. Missions accomplished, they flew home heroes.

##no-place

The feeling that steals over me in many new buildings is of being not so much in a place as in a CAD design.

This notion first occurred to me, appropriately enough, at IBM’s then-brand-new complex upstate, where Shelley and I were presenting our work at the 1998 Governor’s Conference on Arts & Technology.

As I looked around conference rooms and corridors and atrium, the details of the architecture seemed to betray their origin in the synthetic 3d views of a cad program. Every structural and decorative “touch” was precisely what had never been touched — so that it all felt overly clever yet cookie-cutter.

diversion

As a poor visitor to — or, God help you, occupant of — a no-place like this, you can amuse yourself by searching out all the vantage points never considered in the architects’ previz (much less featured in their client presentations).

It’s in these in-between spots that such schemes go horribly wrong, their logic confounded as real space asserts its awkward materiality.

corporate acquisition

On that same weekend at IBM, I was walking down one of a bright fluorescent corridor when several painting adorning the white walls caught my eye.

Looking more closely, I confirmed that they were by Alfred Jensen, whose eccentric numerological pieces I’d just been out to inspect first at the Newark Museum of Art and later at his widow’s house in a nameless New Jersey suburb.

I guess this made some sort of sense to IBM’s art acquisition people, since Jensen looks data-driven, as indeed he is, in a kind of crackpot way — Mayan calendars, Egyptian cosmology, Arabic and Chinese number systems, Goethe’s color theory, Pythagoras, all played a part in generating his grids of colors and symbols.

But the power and immediacy of his canvases were neutered there in that sterile corridor, not only because the fluorescent light flattened them down to dullness, but also because the institutional framework simply overwhelmed them. They looked sadly orphaned & diminished, which is how I’d started feeling by then too.

worldviews

The least likely of our artists’ residencies was claimed by Shelley Eshkar when in 2000 he lugged his computer up to the 92nd floor of Tower One of the World Trade Center to start working on a prototype of Pedestrian. An apt location for a piece that was to take a bird eye’s view of the city (though from a humbler elevation).

The residency program, LMCC’s World Views, of course ended the following year on 9/11, which took the life of one of the artists there and the work of many others.

homeland security

In the immediate panicked aftermath of 9/11, the government established a new federal agency, the Department of Homeland Security, and as I recall it was not long after that that Shelley heard they were looking to decorate their new headquarters with patriotic art.

Nothing could be more fitting, it seemed, than to select artworks that had been created on the very site of had been reduced to Ground Zero, that void of sadness.

And so for a brief while we entertained the idea of creating prints for the offices and corridors of Homeland Security, with the odd and downright ridiculous notion that these works could themselves look on and bear witness mutely to whatever ended up going down there.

In the end, however, nothing came of these prints nor, so far as we knew, that art acquisition program.

## building betrayal

Often it’s with a sinking feeling that I watch a new building rise to completion — each time it’s like a promise betrayed.

For it all starts out so well. The hard-hatted workers with their bright yellow machines dig their way layer by layer down into the dirt, Lilliputians drilling or blasting any bedrock in their way, and all to make a big fantastic hole in the ground.

No wonder that children are so drawn to the little knotholes and windows in the plywood fence securing the construction site perimeter: what they behold below resembles nothing so much as their own sandbox creations, but on a massive scale they have only dreamed of. This raw foundation is a hole that punctures for a time the otherwise impenetrable surface of the grown-up world.

Nor is the next stage of construction any worse.

The effort changes direction, aiming skyward, to create another spectacle: the action of the gigantic cranes, steel girders swinging through the air, the methodical erection of a framework that rises level by level to who can guess what eventual height, with the workers clambering precariously across its beams, the welders sparking their little blinding points of light… and then, as progress continues, the addition of temporary exterior elevators and the beginnings of permanent floors, as this vast vertical space is gradually colonized and settled.

When the construction quits for the day, the incomplete and see-through structure still invites the eye and the imagination to dwell there, flitting through levels and sections, freely picturing any number of future outcomes.

But now come the cement mixers or the bricklayers or whatever, compelling in themselves but signaling the beginning of the end. The building now starts closing down, clothing itself with the usual mundane exterior, and also (one can’t help but feel) stifling and suffocating the eventual humdrum life inside as well.

When the building stands complete, it’s as indifferent to the world as we now are to it. Everyone goes about their blind business again, and the child whose hand I hold stares down at the cracks in the sidewalk.

##point

In the rosy light of early dawn I looked back from the Triboro Bridge towards Manhattan. The view I took in was of the classic midtown skyline, but as my eye wandered north along the East River shoreline, I again noted the ugly high-rises that have sprung up there — undistinguished buildings whose ugliness derives from the bristling of balconies jutting out from every floor. Wherever your eye expects a clean contour, it meets a jagged one instead.

Yet if it’s these balconies that spoil your view, you realize that they’re built precisely to afford great prospects — not of each other, but rather of the vistas stretching beyond them: the city itself with its skyscrapers, parks, waterways, and outlying boroughs, and with horizons not to be seen from the street level below.

Surely, it occurred to me, this was an apt metaphor for a conflict both deeper and more widespread — the glory of privileged position versus its oppressiveness, all determined by one’s vantage point, upper echelon or low.

spire

Answer with the spire: that skyward-reaching point so sharp that only the spirit (but no body) can perch there.

##truer walls

Six weeks’ service on a Grand Jury convened at the Special Drug Court in lower Manhattan entailed much sitting around, a confinement completely negligible compared to what was in store for most of the accused, soon to join the truly staggering number of prisoners that the United States, alone in the world, has been busily putting behind bars for decades now.

Still, our confinement was boring enough, propelling many of us towards inward escapes: crossword puzzles for some, writing for me.

From time to time we’d stir to collective life long enough to follow and then to rubberstamp a prosecutor’s invariably unchallenged indictment of some small-time drug dealer or abuser. Various undercovers (as they were called) came to testify, and it was these faces of the War on Drugs that proved most surprising — had we been anywhere else, I’d have have never guessed they weren’t truly the college student or junkie or handyman that they impersonated so expertly (or were so close to actually being).

Looking out the windows of my apartment in the evenings afterwards, I’d wonder who in the parade of pedestrians on Amsterdam Avenue below were themselves undercovers — or, for that matter, the petty criminals they pursued (since not a few of the arrests chronicled downtown were made in or near our neighborhood, notwithstanding its accelerating gentrification).

I work at home, which all too often means that I pretend to work: idly looking out the streaked windows or gazing at the pockmarked walls — hoping that at least a few of my ideas actually take wing without immediately escaping me. Naturally it was this apartment — these surfaces, these spaces, these shadows, and these views — that I pictured when piecing together Housebound’s sentences and shot-list. Still, when I took out a camera and peered at the place through an actual viewfinder, I discovered its shortcomings. The shots I framed were inevitably too cluttered with family possessions, and no composition was quite clean enough, by which I mean emptied out.

An alternative location came to us almost immediately upon Shelley’s placing an ad on Craigslist — a nearly identical prewar apartment thirteen blocks north of mine, with the same southeastern exposure, but with more dramatic views over Broadway rather than Amsterdam. The family living there vacated the two front rooms for us, and this is where we performed our complicated stereoscopic shoot.

This location proved superior to my place in every respect but one: its walls, unlike mine, had been re-sanded, re-plastered, and re-painted in someone’s recent memory. Thus they lacked the singularity of the walls I am used to — walls that bear traces not only of the many lives lived within them over the years, but even (or so it seems to me) of the innumerable thoughts that have bounced off or been absorbed by them.

In short, such walls as these are true the way that a man or woman’s wrinkles are.

trued

to true a wall, however, means quite the opposite of what it should.

I remember being struck by the phrase one night in the early 90s when I was still new to the city. Perched uncomfortably on a Frank Gehry cardboard chair, I was mutely following the dinner conversation of middling but affluent artists and their partners. We were gathered at a MacDougal Street townhouse bought by our host (a painter) in the flush of the 80s art market.

The talk was less of art than of home improvement, though the latter phrase was not one they’d have used — and in any case the two categories proved nearly interchangeable here. truing the walls and corners of any given room was evidently a near-sacred task, as were a host of other aesthetic interventions that I can no longer recall.

These artists aspired to live in a kind of spatial (and decidedly materialist) utopia, as if they might inhabit the stripped-down spaces of Minimalist sculpture (of Donald Judd’s, especially). One spouse summed up the whole evening with the glib remark that all artists, no matter how impoverished, instinctively master the art of fine and simple living.

trued walls, indeed.

settling

This old building keeps settling into its foundation in much the same way that I keep settling into my chair, trying to find just the right position for my creaky skeleton, worn out from hours of reading and daydreaming.

##model memorial

From time to time Martin Luther King’s three surviving children fight over his spoils., their unseemly squabbles over money and power landing them all in court and dishonoring their parents’ legacy.

There is a sort of monument to that dishonor, the King Center in Atlanta, which I visited around 2004. At the time still under the family’s private control, it was a badly designed and poorly maintained theme park, with the parents’ tomb set out in a long pool of water the color of a chlorinated swimming pool, and a hackneyed International Civil Rights Walk of Fame that aped the much older Stars Walk of Fame on Hollywood Boulevard.

A cold wind happened to be blowing across the desolate expanse of the place that day, and King’s powerful spirit could be felt only in its utterly forlorn absence.

library

This brought to mind another place named for King — the Martin Luther King Jr Memorial Library in Washington dc.

This is a crypt-like building with brooding dark glass set in a grid of dark steel. Its main entrance is recessed below the out-jutting mass of the upper floors, and I well remember the feeling of dread I had on first approaching it.

This was around 1973 or 4, when the building was still brand-new. Already, however, it had a feeling of dilapidation, with its elevators and its hvac systems frequently malfunctioning. No connection was evident either to its purported hero nor to its surroundings, where the ground floors of old buildings were tenanted by a striking number of wig shops and record stores perpetually on the verge of bankruptcy.

With my usual ignorance of star architects, it was only on reading the library’s Wikipedia entry just now that I learned that the design’s mastermind was none other than the illustrious Mies van der Rohe. And that this was his last building — a fittingly disconnected tomb for a certain kind of aesthetic ambition.

a book

But it was on one of my initial visits to this library that I encountered a haunting book that I’ve kept in mind ever since. The first glimpse I had of it was in a thumbnail review that happened to catch my eye as I leafed through the exotic pages of the Times Literary Supplement (dense newsprint on stock so light as to be translucent, the pages fluttering from a traditional wooden newspaper stick).

The book in question, AR Luria’s The Man with a Shattered World, was the neuropsychological case study of a Soviet soldier irreparably brain-damaged by machine-gun fire. Why such a book should have caught the attention of a questing teenager I don’t know, but it led me first to an obscure section of the library stacks to retrieve it and then to one of the reading areas (populated by a roughly equal mixture of scholars, pensioners, homeless people, and junkies) to read it.

To read is to try putting yourself in the place of the writer, but here my effort quickly doubled back onto the act of reading itself. For early on the first-person sections of the book had me imagining myself scanning through its lines (or rather its letters) in the same way Sublieutenant Zasetsky would have had to, three letters at a time, with the focal point displaced up and to the right, as I’ve clumsily diagrammed above.

Sitting at a chair with the book resting on the table in front of me, I also had to try picturing myself suddenly becoming very tall, but my torso […] terribly short and my head very, very tiny — no bigger than a chicken’s head.

Or to imagine other hallucinations of my body image, from which my entire right side could suddenly vanish or in which my limbs could arbitrarily reposition themselves (my right leg, for example, hanging out above my shoulder).

I was also obliged to try matching this kind of constant perceptual instability with similar cognitive lossses — with no piece of knowledge ever securely in my grasp, fighting over and over again to reclaim territory I thought I’d long since mastered: basic literacy, the facts of my life story, etc.

a tomb in miniature

Mallarmé proclaimed that a book is a spiritual instrument — a tomb in miniature for our souls.

The Man with a Shattered World is both of those things, though in saying so I’m willfully misapplying Mallarmé’s Symbolist notion. The power of Luria’s book comes from its plainspoken and hard-won truth, illuminated from the inside by the patient’s relentless determination and from the outside by Luria’s informed compassion.

Zasetsky devoted his life to slowly piecing his memories together on the page: first into words and then into phrases and finally into sentences. Luria reports that he started this story before the war ended and continued to work on it for twenty-five years. He goes on to remark:

One would be hard put to say whether any other man has ever spent years of such agonizing work putting together a 3000-page document which he could not read.

Luria however could read it, carefully and knowledgeably, and in so doing turned himself into the other unassuming hero of the work. He wrested case history 3712 from utter obscurity by excerpting, organizing, and explicating his patient’s writings without ever reducing the man himself to a mere compendium of damage and symptom.

His modest volume is the model memorial.