Devil’s advocate

For a commemoration of John Cage at The New School in April 2012, I composed and then presented the text that follows:

Introduction

One of the most admired artistic figures of the 20th century, John Cage was himself a great admirer — he gave his unwavering devotion to a few chosen heroes. Introducing a text he called Empty Words, he said he’d based it on the initial thought We connect Satie with Thoreau, a link between two of his heroes that probably only Cage would have made. But then he added in a characteristic twist that each section of the work was relevant or irrelevant to the subject.

I could say something similar about my talk on Cage today, that its sections are either relevant or irrelevant to the subject. But I’d put it less categorically: The sections I’ll present to you will have some bearing on Cage, but some will be obvious and others pretty far from it.

I should also warn you that I myself am not an unqualified admirer of anyone, and hero worship makes me distinctly uneasy. You’ll find that I subject even our great man to some serious qualification.

But not right away.

Some skeptics claim dismissively that people preferred what Cage said to what he did — that his theories went down more easily than his music. If there’s some truth to that, it’s also more importantly true that the form of Cage’s words so often embodied his ideas that the two things were inextricable — beautifully so.

Cage composed with words. Unlike many of his mainstream literary counterparts, Cage brought to writing a deliberate rigor of composition, never relying on the lazily inherited structures you find in most novels and essays.

I will try to live up to his example here — which is why I’m not simply talking through a set of ideas and examples, but rather reading words that for once I’ve taken the care to write out in advance. The composition I’ll present is divided into 16 sections, arranged according to rules aimed at generating variety and surprise.

The billing for this talk gives its title as Not Wanting to Say Nothing about Cage, obviously a play on words — rather a silly one, with its awkward double-negative — a play on Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel, which as you know is what Cage called the piece he made here at the New School following the death of another object of his undying admiration, Marcel Duchamp.

I should tell you, though, that during the writing I had two different working titles. The first was Listening and Persuading.

The second, which stuck, was Devil’s Advocate

— my thought being that the devil has a talent for seeing the darker sides of things that we happily suppress. It will be up to you to decide what in this is devilishly unfair and what is not.

### 1. silence ( X000 )

Once upon a time, there was a defense attorney so gifted in logical analysis and so convincing in emotional persuasion that he prevailed in every single one of his cases, no matter how glaring the guilt of his client.

A sharp fellow, by his first week in law school, he’d realized that the prosecutor’s obligation to prove guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt” imposed an impossible burden, so he aimed for the other side of the bench.

One of his tactics was to raise objection after objection, technicality after technicality, point of law after point of law, so that prosecutors could never get into the swing of their argument and jurors could never feel or follow it.

I object! became his automatic reflex, and he was successful and wealthy beyond his wildest dreams.

It was only when he could no longer confine his objections to the courtroom that his troubles began.

— OK, that’s narrative premise, from which we can springboard into any number of stories across a range of genres.

For example, domestic drama: when during his own wedding the priest repeats the customary invitation to “speak now or forever hold your peace,” he, with a cry of “I object!” can’t stop himself from finding fault with his bride, with screams, tears, fingernail slashing, and the hell of a woman scorned in consequence.

Or a medical drama. Fallen ill, he objects to every medical diagnosis and procedure, always seeking a second, third, and fourth opinion, and in this fashion earns an early grave.

Or this science fiction idea: on an airplane flight he begins questioning and casting doubt upon the aerodynamic principles of aviation. Soon we see him plummeting through the skies to his death below — the only passenger to do so!

Or what about a romantic tragedy, told successively by his frustrated lovers? In bed, he objects to each partner on any number of grounds: appearance, age, gender, dominance or subservience, choice of erotic position, effectiveness of contraception, the very need for contraception, and so on.

Naturally this leads to impotence, which keeps him from passing on his traits genetically. But by then he is a legend in the law, and a whole generation of law students grow up to model themselves on his example, with hopes of attaining his level of wealth and celebrity.

The sequel might be a best-selling murder mystery, in the popular serial killer subcategory.

You can imagine that with all these clever defense attorneys successfully defending the accused no matter how heinous their crimes, soon even the most brazen criminals roam free.

And now one of these felons turns into a serial killer, and here’s the real twist: this one’s perversion is that he preys only on defense lawyers. He proves as effective in hunting each one down as the next one on his list is in defending him in court.

But eventually there is no next one, the killer’s deadly path having eliminated all such and thus tipping the balance of justice to the other extreme. Prison cages all across the country are filled to bursting with clamorous crowds of the guilty and the innocent.

###2. caged and uncaged ( X00X ) Caged in a dark room, the pupils were kept in “classes” of about six apiece, where food and music were provided at the same time. As soon as they started to copy a few notes of the song played in the dark, a little light was let in. And so, slowly but surely, sunlight filled the room as the song was fullly sung.

Other teachers took a different approach to musical training, using torture to achieve beauty. Starving their students, they cloaked them in complete darkness till they could sing what they heard.

A true story, though the passage has been slightly smudged and rearranged to cloak the identity of these caged pupils. As you may have guessed, they were songbirds — starlings. Their schools were German songbird academies, in operation for centuries until just a few decades ago.

David Rothenberg, who recounts all this in his book Why Birds Sing, also tells the story of what once happened when a caged bird was set free again.

This was in Australia, in the 1960s, when ornithologists were bewildered by the unusual flutelike songs sung by a regional flock of lyrebirds.

Their detective work ultimately led them to this explanation: Thirty years earlier, an Australian farmer had kept a lyrebird in a cage for a while, and during its period of captivity, the bird had learned to sing parts of the tunes the farmer played on his flute.

Eventually the farmer uncaged his bird again, who brought this new music to the other lyrebirds dwelling in the forest nearby, where three decades later their singing entranced a new audience: scientists doing their fieldwork.

Further analysis of the lyrebirds’ songs showed that the lyrebirds had generated them from elements of two pop songs of the Thirties, Keel Row and Mosquito Dance.

Which makes one wonder: If the academy cages a mosquito, can they teach it to dance?

4. scrambled words ( X0X0 )

I’ve often remarked on Cage’s odd way of demonstrating his heart-felt devotion to the writings of the men he revered.

He mangled them — and not once, but repeatedly.

Having invented his practice of writing through a text — cutting up its words and letters at random — he took his tender knife to both Joyce and Thoreau.

Before continuing, however, I should give the man his due:

Reading Thoreau’s Journal, he wrote, I discover any idea I’ve ever had worth its salt. This quote of his caught my eye on the back of a Thoreau compendium two years ago, and I owe to Cage my intense fascination with the Journals ever since. Entries like this one

have led me to regard Thoreau’s personal writing as the high mark of American prose.

But how did Cage read Thoreau? Or — to put it more precisely and more peculiarly — why did he decide to read Thoreau this way to us?

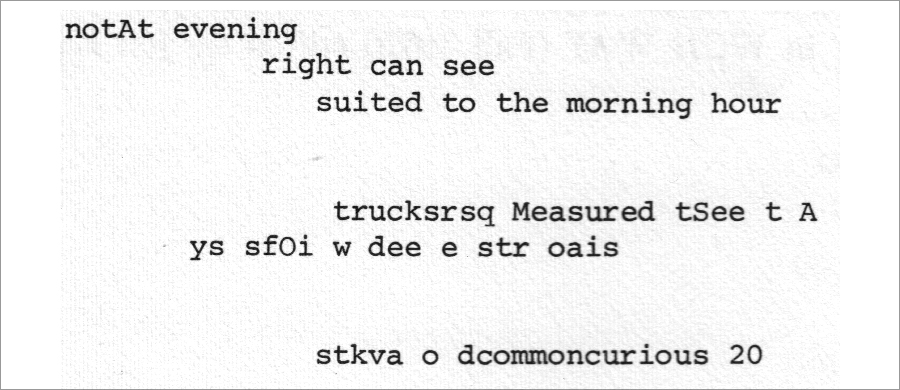

The longest writing-through-Thoreau he executed is called Empty Words. Here’s how it begins:

Even worse, here’s how it ends, several sections and many pages later:

It’s strange how so many of Cage’s homages to his heroes render them incomprehensible.

If you’ll pardon the pun, he cages them in his own style of composition.

Still, it’s fascinating to see how one intelligence can seize what it wants from another.

5. missionary work ( XX00)

It so happens that Jesuit missionaries reached the Sierras of northwestern Mexico as early as the 1600s, where they converted many of the Tarahumara Indians they encountered there to Christ.

Not long afterwards, the Jesuits up and left again — the King of Spain, following a papal edict, had booted them out of his empire. They were not to return for nearly a century.

When they did make their way back to Sierras, they must have been pleased by what had stuck there: religion and music. To this day, the Tarahumara perform one style of music very different from the others they play.

Called matachin music, it’s performed by the men while the women dance. From their oversized fiddles comes a music that has gone its own way between distant cultures and eras — a beguiling mutation of the Spanish folk tunes that seeded it centuries earlier.

The matachin music is the Tarahumaras’ wordless contribution to Catholic mass, during which they still count on Jesuit priests to speak the holy prayers on their behalf.

6. the elect ( XX0X)

When he was young, he felt the missionary spirit already strong within him, and he devoted his life to converting the world to his views. He evangelized the doctrine of non-intentionality, but the fact that his purposefulness contradicted that doctrine never troubled either him or any of his followers, of whom there were eventually a multitude.

Like any true believer, he bowed down to certain prophets, devoting himself to them as unquestioningly as he persuaded others to do. Some of the elect were avant-garde artists like him (Satie, Duchamp, Joyce), while others were religious scholars (DT Suzuki), and still others utopian futurists (Norman O. Brown, Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller).

A disciple himself, he soon gathered a tight circle of fellow disciples — Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenburg — and together, mainly through the example of their good works but also by means of their mutually reinforcing reference and praise, they rose together to the heights of influence.

Now perhaps it’s time to ask ourselves, When do we stop looking up at them? When do we start looking in a different direction?

7. exchanges ( X0X0)

It’s fascinating to see how one intelligence can seize what it wants from another — and vice versa.

I once came across a claim that the starling’s song is at the very limit of human comprehension.

The explanation was that starlings sing at such fast speeds and at such frequently high registers that our ears can barely track them. They also improvise constantly — and they do so by drawing from a bewildering number of sounds in the world around them. If you listen closely, you can hear them busily interweaving fragments of other birds’ songs as well as snatches of human speech.

Listen even more closely, and you may hear a teakettle whistling, a doorbell ringing, a neighbor sneezing…

In doing research for a public artwork we made for the Mostly Mozart festival a few years ago, I’d discovered that Mozart himself had cherished a pet starling from the moment he first heard it singing in its cage in a store.

He could hardly believe his ears, for it was singing a theme seemingly snatched from one of his own piano concerti (K 453). Every note but one was the same : the starling had made Mozart’s G into a G sharp.

Mozart must have said to himself, how did that bird get my song? Had it heard me whistling it in the street?

At any event, the composer bought the starling and took it home with him. And when it died a few years later, he conducted a full mock funeral service for him, reading a poem he’d composed as its eulogy. A week later, he completed a little composition (K 522) that scholars suspect to be his own musical mimicry of the starling.

Marc Downie and I took all this as a point of departure for one of the tall light boxes we constructed at Lincoln Center. In it, we pictured an imaginary starling making sense of what it heard — and then recomposing it in song. The twist was that we had our conjectural bird listening to the German poem Mozart had written in lament for his starling.

Below the poem, we made an inverted tree diagram that showed the imaginary bird’s primitive parsing of the poem’s rules of syntax. After formalizing its own understanding of the poem’s composition, our starling could re-arrange and riff on on it, a performance we visualized in variations climbing to the top of our depiction.

Now Cage hadn’t come to mind when we were doing this, but I doubt we would have gone down this route without his prior example.

But may I point out a difference in approach? If I’m not mistaken, our starling-writing-through — even though purely made up — still mirrors the way a starling really sings much more truly than Cage’s writings-through reflect the way a person really reads.

8. the deal ( 0X0X)

The plea bargain having been placed on the table before him, he closed his eyes and said, Give me a moment to think.

Time weighed heavily on him — and on her.

As she studied his face, she felt her fate hanging in the balance and wondered once more whether he was really capable of —…

— With this unfinished sentence glowing on his screen, he’d nearly reached the climax of his novel, the moment of truth.

He wondered whether his dream of a jackpot would soon come true: whether Hollywood would option his novel, stripping its flesh down to the skeleton of a screenplay, and pushing his lines through the mouths of actors to reach movie theaters and living rooms throughout the land.

Though my hackneyed novelist didn’t formulate his thoughts like this, couldn’t you say that in the same way that a tree puts forth its seeds in tempting fruit so that birds will eat it and then scatter it far and wide, so too should you find forms for your ideas so intriguing that others will bite — bite, swallow, digest, and spread, one mind to many others?

9. bizarre rites ( X000)

To worship a saint means to venerate every trace of his or her existence.

Believers collect physical traces of a saint’s life in sacred reliquaries, which can house such things as fragments of a skull, flakes of a bone, and spots of blood on a scrap of clothing.

To truly admire a man is to believe that everything he did was precious. That whatever you can do to resurrect any bit of his existence will be rewarded.

There’s something of the spirit of all this in Cage. Take for example his approach to Duchamp.

Early in his career, Duchamp had composed several musical pieces entirely by chance, and it was natural for Cage to later champion these works and this approach, which anticipated his own by decades.

A small story about Cage regarding Duchamp tells something a bit more peculiar, however. Fond of disguises, it had turned out only after his death that in his later life Duchamp’s outward activities of idle cigar-smoking and disinterested chess-playing merely concealed his real undertaking. Despite his public renunciations, he’d been working as an artist for years in a secret studio known only to him and to his wife.

It was there that he was able to complete his final artwork, the Etant Donnés, without anyone knowing the better. Duchamp had made secret provisions for the piece to be transported and reassembled in the Philadelphia Museum after his death, and he entrusted to the museum director a notebook with precisely illustrated instructions for installing his posthumous creation.

Learning after the fact of the existence of this notebook, Cage insisted that the museum director have it published as a key Duchamp document.

Half-joking but completely serious — as was his way — Cage made the claim that the incidental sounds of taking the piece down in the New York studio and putting it back up in the Philadelphia museum would be inherently musical — in fact would comprise the most musical of Duchamp’s complete works.

This is a far cry from supposing that all sounds have equal value, no?

What’s weirdest is Cage’s willful blindness to what Duchamp’s final work might mean, why the two peepholes in its door reveal a trompe l’oeil scene that has a stripped and headless woman extending her spreadeagled legs toward you.

I suppose it’s not surprising that Cage, who to my knowledge never alluded to any kind of sexuality either gay or straight in his own work, would not seek it out in others — but what did he think when he studied the pages from the notebook that he’d rescued from obscurity and then revered?

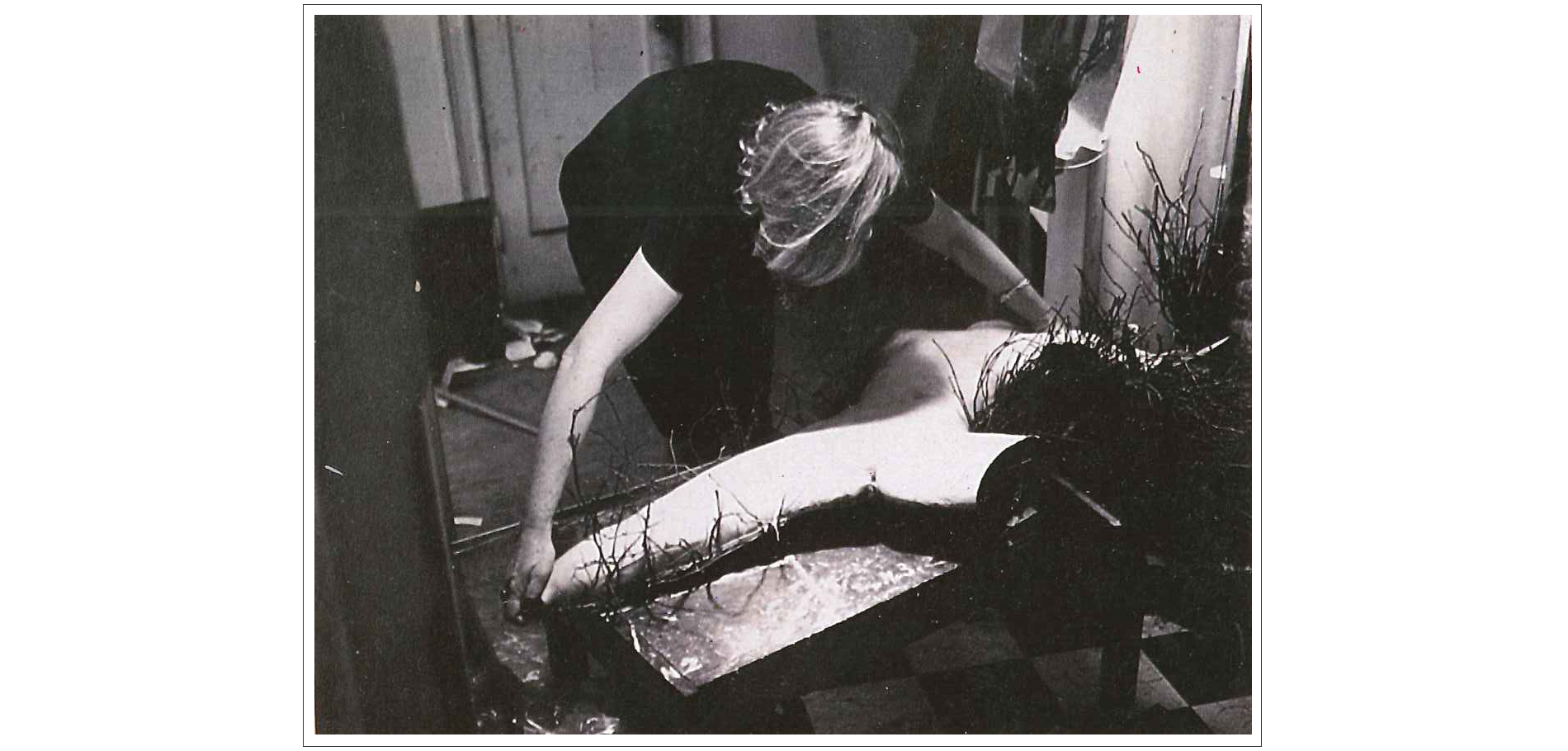

Some of the illustrations show a figure who must be Duchamp’s wife, Teeny, who’s arranging that torso and legs for her husband’s snapshot — and what could she have beeen thinking then? For the bare body is modeled after Duchamp’s previous lover.

And what did Cage make of lines like these from Duchamp’s instruction manual? Did he perform chance operations as he was reading them so that he could blind himself to what they said?

Place the forearms on the small wooden bar very tightly screwed to the table from behind.

Note carefully how the wooden bar inserts into a small cup of dissolved metal in the forearm.

— One more story. Several years ago I leafed through a remaindered book that I should have bought on the spot. Called the Exquisite Corpse, it charged the infamous Black Dahlia murder in Hollywood in 1947 to the influence of Surrealist philosophy and aesthetics — the murder and the display of the corpse probably regarded by the murderer as his art work.

Supporting evidence came from the the fact that the murderer was a friend of Duchamp’s pal, Man Ray; which raises the question whether these crime scene photographs may in turn have fed Duchamp’s last work.

Guilt by association, you might say. Not enough to convict by a long shot, but… — but when Cage gleefully urges the separation of form from meaning, you should know that that can be a really bad move.

10. anarchic fantasy ( 0XXX)

As a kid, I was entranced by a little gift my grandfather gave me, the Audubon Bird Call, which was as simple as it was effective.

Just turning a little metal crank that rubbed up inside a small wooden disk, I could (like magic!) conjure up an amazing range of seemingly realistic birdcalls — realer than real, it seemed to me, for the sounds seemed more vivid than any I’d heard real birds making.

Some of the birds around me in the park started responding to the squeaks and whistles that I was randomly making as if they made new but perfect sense, and before long all sort of novel matings and alliances had formed, forever mixing up their established territories and bewildering the local bird-watchers.

So at least I imagined. From there, my dreams of revolution grew bolder. Had I not discovered the secret to remaking the world — through chance operations?

11. not listening ( 0000)

- Saying I can’t hear myself think, he puts his hands over his ears.

- Saying I can’t not hear myself think, she chants her mantra over and over and over to herself.

12. sound and meaning ( XXX0)

Following college, I’d gone to tape-record the matachin music of the Tarahumara Indians, where two weeks later I succumbed to the food poisoning that awaits most gringos new to Mexico.

Soon dangerously dehydrated, I was trucked down the dirt road to Sisoguichi, the town in the valley where the Jesuit Mission and the state infirmary lay. The seven beds of the men’s ward were all occupied, and from two of them came cries and moans that punctured my own delirium.

As I recovered I learned that in one of those beds lay a young boy receiving the very painful course of treatment for rabies: a series of something like twenty needle sticks in his belly. In the other was a young man who’d been riding a horse across a field when struck by lightning and hurled to the ground.

Could it be my imagination now or was it my imagination then? — that in my delirium I imagined the sudden snarling of the rabid dog just before the attack and the fateful bite — or the crack of thunder booming through the sky overhead, too late a warning to the man writhing below.

13. meditation ( 000X)

You sit outside to meditate, ears open wide. The crack of thunder is distant and the lightning has struck someone else.

In the traffic island, you can hear birds twittering and singing overhead, and certainly this, you think, is a beautiful music with its randomly shifting polyphony and call-and-response duets.

For the sake of your serenity, it’s a good thing you don’t understand the language of birds, for the one in the tree overhead is sounding an alarm (hawk overhead!), while the one over there is shouting at his rivals, this territory is mine and mine alone!

The voices of passersby now drift past, and you manage to attend only to the sounds of their syllables and not to the sense of their sentences, avoiding entanglement in their glimpsed lives and stories.

But then you gradually acknowledge to yourself that there are sentences others are still speaking within you. You hear the injunctions of your musical or your spiritual guru, in whose frame you are sitting and whose words and image and story hover all around you, just as they do in the concert hall, museum, or church.

With this realization, your mind goes its own way.

You wonder how to lose all awareness of the one mastering you, mastering you even from beyond the grave, and whose message, you feel, you’ll never master yourself until you’ve fully expelled him from your head.

Upset, your thoughts gnaw on the idea of purity and you wonder whether the art of abstraction is really possible.

You remember the time in Moscow when you finally stood before the pinnacle of abstraction, Malevich’s Black Suprematist Square. The black paint had cracked into fine white lines crisscrossing the square, and in dismay you realized it’s only the idea of its purity that remains.

And now this idea is just one among many in your mind, and it attaches itself to other stories you can’t help but follow — for example, the sad fates of the Suprematists themselves in Stalinist Russia, reflected somehow in the deserted shabbiness of this white elephant of a museum…

But with a jerk, you bring your mind back to your meditation, trying again to achieve the perfect blank.

14. a bedeviling question ( 0XXX)

No need to introduce myself again; I’ll only be here long enough to prosecute rather than to defend the case before you.

Only one legal question is at issue:

- Should the leaders of a movement be charged for inciting the crimes of their followers?

I shall prove Cage guilty for inciting the numerous copycat crimes committed by his followers to this day. These crimes violate the rules both of logic and of morals, and I will show beyond a reasonable doubt that they spring from a single insidious source: the splitting of form from meaning, an idea that Cage became so adept in selling.

Wish me luck in the courtroom — not that I’ll need it.

15. retrieving structure ( XXX0)

Here’s the story of how I made this talk.

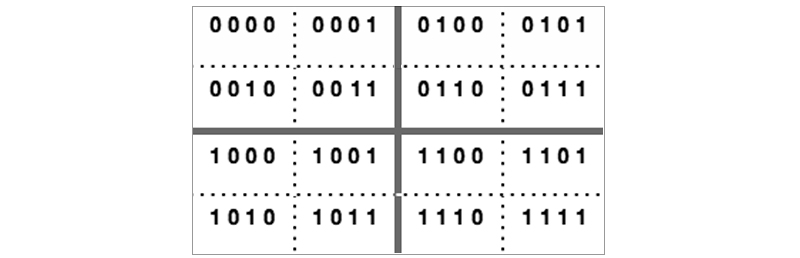

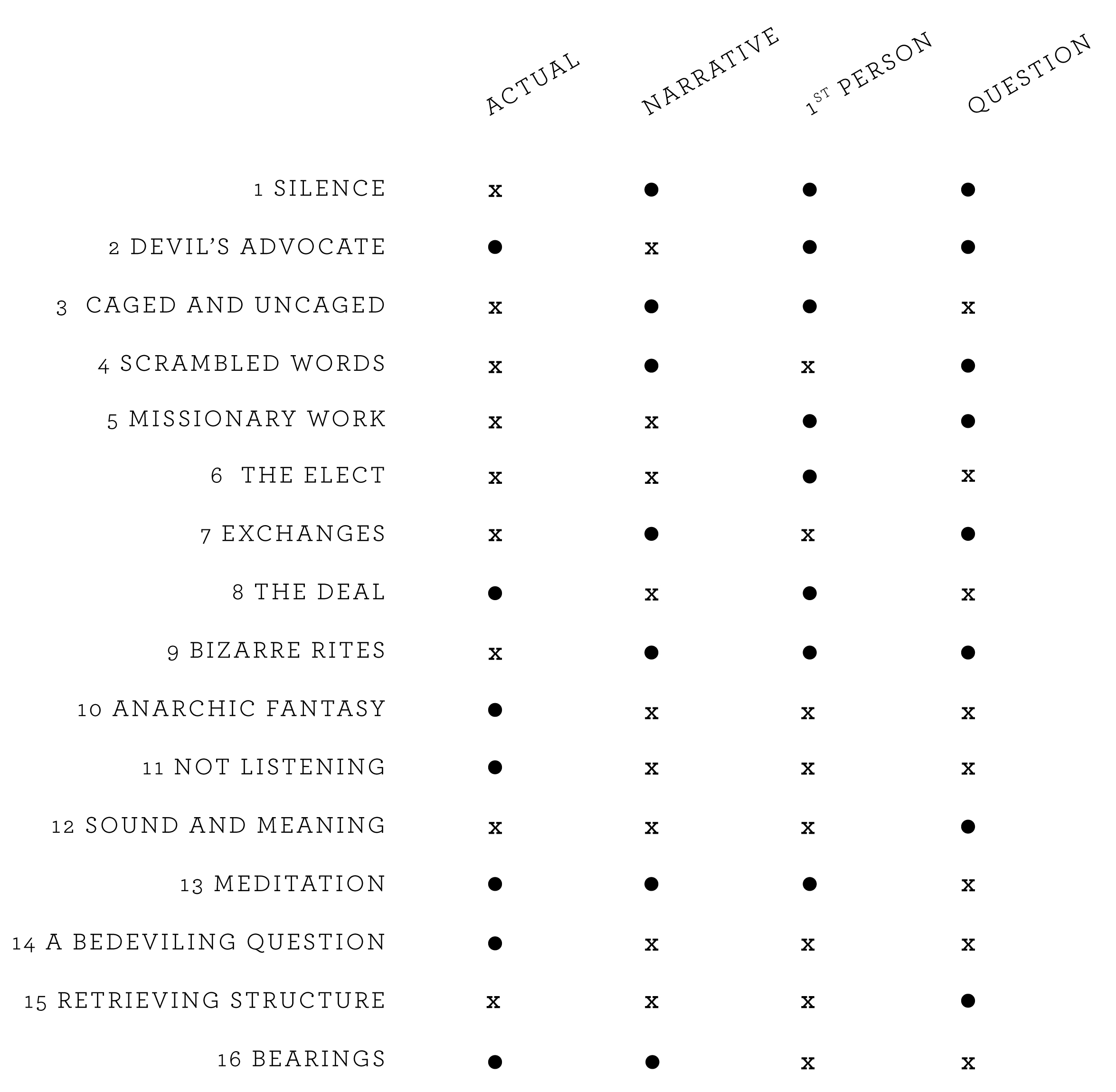

I’d decided to impose a Cage-like challenge on myself by setting up a system of rules for my composition, rules intended to create the unexpected. Each section was to have a configuration of attributes different from those of the other sections in at least one way.

My colleague Marc Downie explained to me that in order to exhaust 3 attributes I’d need 9 sections, to exhaust 4 I’d need 16, for 5 I’d need 25, and so on in a progression of square numbers.

Sixteen sounded about right for my purposes, so eventually I settled on these four properties:

- Was the passage to be about something real?

- Was it to tell a story?

- Was it to be told in the first person?

- Was it to end in a question?

Next I needed to generate all the combinations of these attributes, with 0 = Yes, and 1 (or x) = No.

Marc ran the matrix for me, which yielded this string of unique combinations: 0000, 1001, 0100, 1101, 0010, 1011, 0110, 1111, 1000, 0001, 1100, 0101, 1010, 0011, 1110, 0111.

Rather than accept the arbitrary order of the list, I decided to choose freely between them as they fit my purpose, crossing each one off after I’d used it.

Eventually this led to the structure I’ve been taking you through, which looks like this:

Now unlike Cage I don’t follow my own rules religiously, and so when it proved more expedient I allowed myself to use the same variation in both sections 04 and 07, as you can see above. A second duplication, of 01 and 09, escaped my attention until I assembled this chart.

In the end, if there’s a trade-off between meaning and formal perfection, I’ll opt for what things mean.

— But I am still not quite done. As you can see from item 16, this structure demands one more section of me, so here it is — a very short one.

16. bearings (00XX)

When did I stop looking up at them? Was it when I gave up trying and stopped looking at all?

Or was it when I looked off in a different direction? — and realized that that way was up.

Decide this for yourself, a choice that can’t be at random since that would itself be a choice. Which way are you going to start looking?